Henry Jackman on Scoring KONG: SKULL ISLAND

Interview by Randall D. Larson

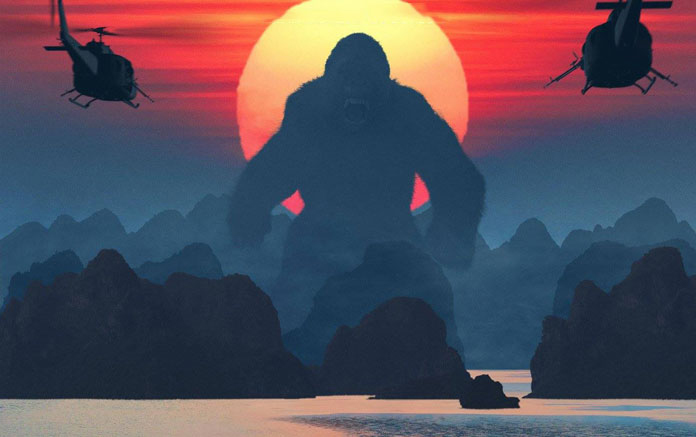

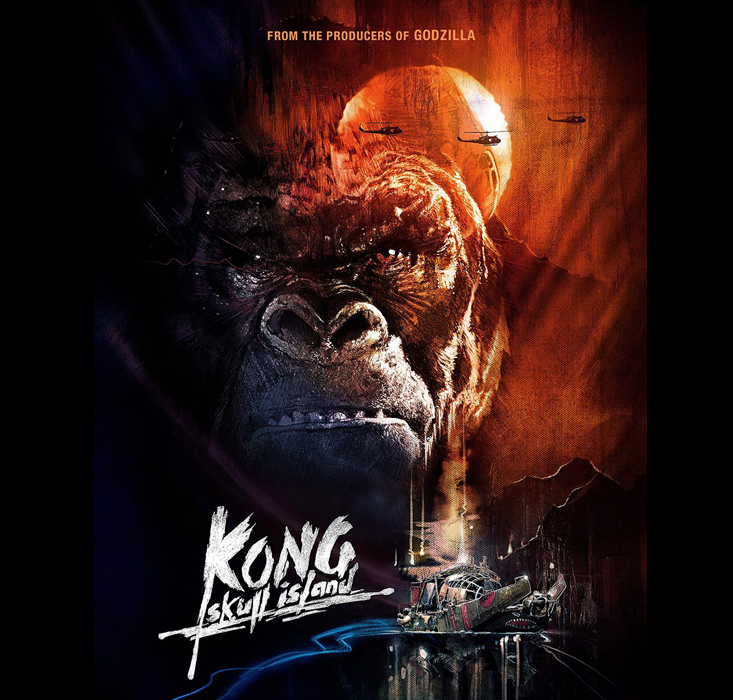

Composer Henry Jackman delivers a powerful score in the upcoming blockbuster Kong: Skull Island. The film is a reboot of the King Kong franchise and will serve as the second film in Legendary’s MonsterVerse, and as a prequel to the 2014 film Godzilla. This is the first collaboration between Henry Jackman and director Jordan Vogt-Roberts. Jackmanstates, “It was an amazing experience to work on a movie whose main character [King Kong] had such a rich Hollywood heritage. Bringing that character into the 21st century meant we were able to use the symphony orchestra one would expect from a Kong film, whilst simultaneously involving guitars and modern electronic elements. Working with Jordan was great – he brought his own unique take on an already established story.”

When a scientific expedition to an uncharted island awakens titanic forces of nature, a mission of discovery becomes an explosive war between monster and man. Tom Hiddleston, Samuel L. Jackson, Brie Larson, John Goodman and John C. Reilly star in a thrilling and original new adventure that reveals the untold story of how Kong became King. The film is distributed by Warner Bros. and opened in theaters March 10th. On the same date, WaterTower Music released the score soundtrack album, both digitally and on CD.

Q: What you came into the project, what was your first inclination of the kind of music this particular property needed?

Henry Jackman: There were two things happening at once. One was the particular angle and slant that the director brought to the occasion, which was steeped in the ‘70s, and that was cool in itself. So you don’t ignore that, musically, because it’s an important aspect to it, but then at the same time you’ve got the heritage and the history of Kong, which stretches way back to the ‘30s. I knew that, on the one hand, I wanted to incorporate period music into the score – and funny enough, so did the director; Jordan [Vogt-Roberts] was great in going “look, we’ve got full permission to explore some psychedelic textures and some guitar elements and whatnot.” But I was also really keen on, yes we can do that but we also need to have the grand symphonic sweep and scope and acknowledge the history. We don’t want to re-mix it so much that it feels too-trendy-for-its-own-good kind of thing. And I think we may have ended up in a really nice sweet spot, because it’s got a few needle-drops [pop songs inserted into the movie soundtrack] from the period in the movie, but when the needle-drops finish it’s not like there are no psychedelic textures in the score, you still get some guitar in the score, but then you also get the full symphonic. I knew I wanted to write a borderline classical Kong thing and then somehow get this whole package of musical elements to work together. And I think we might have pulled it off.

When I came to write the Kong theme I wanted something that was, a: orchestrated fully and symphonically, and b: the psychology of the theme had to arouse a sense of majesty, a sense of sympathy – it had to have emotional resonance, but also needed to feel just “otherly” enough not to be ordinary.

Photo by Melinda Lerner

Q: What was your thought process as you began to come up with a theme for Kong?

Henry Jackman: Kong’s an interesting one, because one of the reasons Kong resonates and has done for decades, is he’s not just a monster. If you keep making a movie and all it is a big, bad scary monster, you’re going to get bored, because monsters just attack and are either defeated or they defeat you. There’s not much to say about a monster. Whereas Kong, even from the earlier ones – the one in the ‘30s, the one in the ‘70s, and Peter Jackson’s – we all know the thing about Kong is, yes he’s a monster, but he’s also majestic and there’s a little sadness to him. There’s always been a beat of empathy to Kong, but he’s not pitiable because he’s so majestic. So when I came to write the Kong theme I wanted something that was orchestrated fully and symphonically, and the psychology of the theme had to arouse a sense of majesty, a sense of sympathy. It had to have emotional resonance, but also needed to feel just “otherly” enough not to be ordinary. The harmonic language used has some tritones in it and it gives it a feeling… because, it’s not every day you go to an island and see a 200-foot ape. I mean, this thing has come from a different era and from a different world, so it has to combine the “otherlyness” you associate with fantasy or something unknown, but also the majesty, the emotion and the sympathy, and, for lack of a better word, the humanity. When you’ve gotten over Kong the Beast, you start to understand him as Kong the Protector and Kong the Guardian of the Island, and you get all these richer emotions coming in. And the theme had to be able to bear all that.

Q: Your score has a massiveness of sound which seems appropriate to the titular character you’re facing, both in large orchestral strokes but also in the intriguing use of strident electric guitar. How did these contrasting factors come into play for you as you were mapping out the score and integrating the two?

Henry Jackman: The origin of the guitar was really Packard’s character [played by Samuel L. Jackson]. He’s a good soldier who’s a little bit lost. There almost a bit of the Heart of Darkness about him. He’s a good man and he looks after his troops and he wants to believe in a straight up-and-down America that sights for good, but Vietnam is a confusing experience. The movie’s set just towards the end of Vietnam and it’s almost like he’s looking to win a battle that he maybe never won in Vietnam, and he progressively is slipping from the path of wisdom into a sort of vengeful mentality. So the psychedelic guitar that becomes increasingly strident and increasingly de-tuned represented his general disillusionment. That’s really the origin of where the guitar really made sense, but then it translated across the score, because Packard is indeed the commander of a bunch of troops, so it made sense that the more straight up-and-down rock thing just permeates through to the military guys also. There were certain cues where if it’s only guitars it’s too parochial and would start sounding like a needle-drop from the ‘70s; if it’s only orchestral it’s going to sound too traditional, so I found a way to get them both going at the same time so you get the individuality and the color of the guitars but then they’re framed in an overall symphonic architecture, so it still feels like a big movie.

Q: Aside from Kong’s and Packard’s theme, how would you describe the score’s other thematic components and their interaction across the arc of the story?

Henry Jackman: There’s a track called “The Island,” which is a sweeping, soaring thing that related more for the overall sense of adventure, not specifically Kong. There’s the whole prospect of discovery and the Island and the general sense the mission, so there was a Mission Theme, and an Adventure Theme, and then there’s quite a lot of gnarly material for the hideous creatures. That was interesting because harmonically I shared a similar language between Kong and the other creatures, but Kong’s theme distinguishes him from the other, more unpleasant species.

Q: Your action music is ferocious but also seems to be tonally or texturally linked to the environment with a lot of percussion and echoes of Kong’s home. How did you approach the tremendous action music in this film?

Henry Jackman: Well, you’ve hit the nail on the head! It’s finding that sweet spot. If it was all just production it would just sound like a trailer and not feel like a KING KONG movie; if it were only a symphony orchestra with no percussion it would sound too traditional, so a combination of using the strength and power of pretty vicious orchestration, but then having the pounding drums… you’re sort of justified in doing that, because there’s something about the Island and the mystery of it where you half expect to be hearing pounding drums of one sort of another! And it’s finding that balance, because if it’s too percussive you’re missing some of the narrative and melodic aspects that can help tell the story, but if you don’t have enough visceral and percussive elements it’s just missing that savagery. And with a little love and care you can find the sweet spot in that.

Q: Who was your guitarist?

Henry Jackman: I was very lucky in that a gentleman by the name of Alex Belcher played a lot of the guitars. To be honest there was a lot of experimenting… we filled up my recording room with all kinds of amps and whatnot, and we often found things that were broken would be especially useful! It’s funny – when you work on movies very often when you’re working on a sound, it’s not really like a record. You’re trying to find a sound not to be a perfect sound but a descriptive sound that helps the character or an aspect of the story, so we were often playing around with de-tuned strings, bits falling off amps; we even ordered a bunch of parts on eBay and assembled a higglety-piggledy amp that we felt would kind of represent what an amp would be like in the 1970s if it was half falling apart! So there was a fair amount of experimenting. By discovering odd tunings of the guitar, quarter tones, or deliberately letting feedback and tonal buzz happen, the sort of things that recording engineers are in a hurry to get rid of, we were happy to get into the sound!

Q: What would you say was most challenging, or most exciting, for you about the process of scoring KONG?

Q: What would you say was most challenging, or most exciting, for you about the process of scoring KONG?

Henry Jackman: The most exciting thing was just it’s being a KING KONG movie before we’ve even come out of the gate! As a film composer, you’ve got a sense of privilege, because all sorts of great movies are made from scripts that people have just come up with or ideas people have come up with and that’s fantastic, you could even argue there’s not enough to that and there’s too much franchise in the world. But in the case of KING KONG, I really felt like I was joining in a noble lineage! KING KONG just feels like it has the resonance of a literary character that’s been with us forever; a character with a great history. So before you’ve even started, you’re lucky to be on it. And for challenge, maybe the biggest challenge was knowing how far to push and pull in each direction; knowing how symphonic to go, knowing how far you could push the guitar elements and where they should go. It’s a push-and pull of how non-symphonic can you get without losing the grandeur and how traditional can you get without losing the originality, and just finding where on the spectrum the two things intersect.

There’s something about monsters which is a good thing for a film composer…

Q: With this film setting up the inevitable meet between Kong and Godzilla coming up some time in the future – would you find it interesting to score that film if you were asked?

Henry Jackman: Oh, that would be a no-brainer! It makes me think of a bigger or more open question, which is that there’s something about monsters which is a good thing for a film composer. You can go back to PREDATOR, and I hold Alan Silvestri’s [score for] PREDATOR in great reverence. People may not think of PREDATOR as one of the classiest films ever made, but I think it’s a great film. What particularly elevates the film beyond what it otherwise would have been is Alan Silvestri’s fantastic score, which uses a really cool octatonic scale and it’s just really imaginative. There’s something about an alien monster or an otherly creature that seems to bring out some very interesting music. It’s because monsters allow this kind of grand scale, especially in 2017 where many films which are contemporary don’t necessarily invite a symphonic grandeur. There’s something about having monsters in a movie that gives permission for film composers to write genuinely symphonic music. I don’t quite know why that is, but given that there’s a real vogue often for very simple ostinatos and a lot of production and powerful, long lines, which isn’t necessarily genuinely symphonic music. The great thing about once you’ve got a Godzilla on the screen or a King Kong, you’re expected to hear music of a certain symphonic grandeur. It doesn’t feel out of place in a way that you couldn’t do in other types of films. So big monster movies are a haven and a compositional oasis to deliver influences that stretch back through the Silvestris and the Jerry Goldsmiths right back to the source, which is sort of late Strauss and big grand 19th Century Austro-Germanic symphonic music, which really can’t find a home in most modern cinema. I mean, try doing that in THE REVENANT! It’s completely inappropriate! THE REVENANT is a beautiful score that has this fantastic minimalist approach to orchestral writing, which is absolutely beautiful and utterly suits it. The great advantage of seeing Godzilla hammering the crap out of King Kong, if that should ever happen, is that it’s a similar thing. It would be expected to be feeling the full force of a symphony orchestra in its full glory and tradition. I don’t know why monsters invite that, but they do – for whatever reason!

Q: Do you feel there’s an added responsibility for a composer because here you have to support the audience’s suspension of disbelief and help make the fantastical situation real?

Henry Jackman: I think, maybe. Well, my attitude is once you’ve agreed to do the music for a film, it’s sort of your professional job to get under the skin of that film and help it 100% in whatever way you can. But you’ve definitely touched on something, inasmuch as in a drama, you very often need to just get out of the way – it’s not about being bombastic, it’s about gentle and subtle support. You’re not part of a conspiracy to persuade the audience of something that is otherwise not possible or real; whereas once as you enter a genre that involves fantasy or the suspension of disbelief, there’s an added job for the music to create a sonic world that seems to represent this otherly and impossible thing and make it convincing. This is another reason why I love Silvestri and his score for PREDATOR – when you have to come up with a language that suggests otherlyness, you can’t just hide behind texture and sound, you actually have to know your harmonies, and one of the ways you can evoke a sense of another world is through the harmonic language. Of course, people don’t know this when they’re watching the film, they’re just enjoying it, but you can end up suspending people’s disbelief by unveiling a harmonic language which just instinctively feels like it’s from another realm. And it’s great because you get to use all these really juicy chords that you wouldn’t be able to use in a more realistic type situation.

I think another reason why monsters give permission, as it were, compositionally, to reach into the tradition of symphonic music, is that very often monsters feel a bit timeless, like they’ve around forever. If you see King Kong he doesn’t feel like he came into being along with the i-Phone 7, you know?! You have a feeling that these are giant, epic, and mythical creatures that almost stretch very far back in history. These are timeless creatures, so I think there’s something mythic about them in the same way if you were representing Zeus or Mount Olympus; it would be unlikely just to be a needle drop, or something electronic. In depictions of Mount Olympus or the Nordic myths, or whatever it is, you expect a certain amount of gravitas and you need to feel the lineage of some sort of tradition. I think that’s why monsters invite a good and sturdy use of the symphonic tradition.

Special thanks to Andrew P. Alderete and the crew at Costa Communications for facilitating this interview. -rdl