Brian Tyler Enters The Dark Universe

Interview by Randall D. Larson

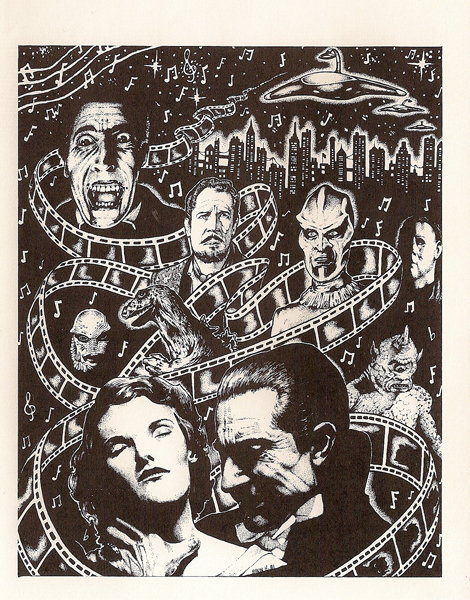

The Dark Universe is Universal Pictures’ new franchise of rebooted classic horror characters that include the Mummy, Frankenstein, the Wolf Man, the Phantom of the Opera, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Invisible Man, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and more. It’s like the Marvel or DC Cinematic Universes only with the classic Universal monsters that launched the horror movie boom in the 1930s and ‘40s. THE MUMMY, which opens today, launches the Dark Universe as an interconnected world in which all of these archetypal monsters coexist and interact. With Brian Tyler’s terrific score for THE MUMMY offering both homage to classic mummy movie motifs and a theme-driven score in the classic mold, the forthcoming movies may bold well for orchestral horror movie music. I interviewed Brian on June 8th, the day before the release of both the film and its soundtrack album, to get some of the details behind his latest symphonic score. -rdl

Brian Tyler: There always is with an undertaking like that. In reality, regardless of the responsibility, you treat everything as the utmost importance, whenever you say “yes” to a project and start to work on it, at least that’s my take on it. So the pressure is always on. I want to do whatever’s best for the movie and give it a voice of its own. In this case the storyline was doing multiple things and one of them was introducing the idea of the Prodigium holding this world of monsters, and that needed its own musical voice, even within the movie.

Q: When you first came onto THE MUMMY, what were your first inclinations of the type of music you felt it needed – or were being asked to write by the director or producers?

Brian Tyler: I’d worked with [director] Alex Kurtzman many times over the years, and we’re both great lovers of cinema in general. We knew this was a new take on it, and you can’t really avoid controversy in that way because you’re stepping into someone’s favorite territory. There have been various different incarnations of THE MUMMY over the years since 1932. We’re both big fans of the original film, and I’ve also kept in mind Jerry Goldsmith’s 1999 MUMMY and Alan Silvestri’s sequel score to that, as well as the more recent incarnations. There are also aspects of films like LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK that have influenced this movie. There’s so much we learn from those who paved the way and certainly in this sense that’s been the case – but at the same time I wanted to establish my take on thematic writing on something like this, which is kind of the combination of horror and romance. That’s something I’m fond of, the idea of an evil that you are drawn to, that has something appealing about it, and that’s why the themes in this film have that dual purpose.

Q: You’ve alluded to the references or nods to the classic Mummy movies of both Universal and Hammer and the Goldsmith score, which I think gives your score a unique reference point to the entire musical history of the Mummy character through its various interpolations. How did you come up with those specific bits and decide where to infiltrate them in your new score?

Brian Tyler: If you go all the way back to the James Dietrich score for the original 1932 film, and then also, later, to THE MUMMY’S HAND [1940, music by Hans Salter & Frank Skinner], but especially the 1932 MUMMY, there’s a certain brooding, unsettling, relentless nature to it. Not just the Mummy’s music but the other music within it, it had an underscore that was very mysterious and even otherworldly in an almost science fiction way. Jerry Goldsmith’s score was also something that I was cognizant of and gave me the idea of doing music mythologically, sounding like it had history to it. That that was something that Jerry was so great at; you can’t really place his MUMMY music in any one particular era, and so my intent with this was to do something that was perhaps a little more difficult, in a practical sense, than a lot of scores done today. I wanted the score to stand as a singular piece of music, by recording everything live, together at the same time, as much as possible. Often you have scores that are very highly produced that record brass on one day and strings on another day, and winds on another. The thing that I realized, listening to the Jerry Goldsmith music, and it’s something that I am an advocate of, especially on this film, was that you can’t always pinpoint the era it belongs to. Part of that is by recording the entire orchestra together. The brass can listen to what the strings are doing and you can subtly adjust your tuning and your playing; there’s a level of dynamics that you’re performing as a brass player, or wind player, or whoever, according to how others are playing in the room. Now of course this makes it a little more difficult in terms of practicality if you want to tear the score apart later, but I think the advantage that you gain is great in that the musicality gives it less of a multi-tracked vibe, less computer-oriented and more symphonic.

And this was even done with the Egyptian instruments. I had them in the room at Abbey Road, playing with the rest of the orchestra. Of course, if one of those instruments plays off it ruins the take, you know, so there’s always the question “why don’t you just track that on another day? Just do that in a small studio, you don’t need Abbey Road for that.” I thought, no, I would rather take that risk because I think of everyone relying on each other and listening to each other… my analogy would be, if you were recording a jazz trio record you really wouldn’t want to record the upright bass one day and the piano on another! The studio and Alex, and also Tom Cruise, who is very musical himself, got behind the vision and we were able to record it properly and I’m glad we did it that way. I didn’t want to date the movie, being that this was something that involved a bigger world and however people accept the movie, or don’t, or however it goes down, you want to put your best foot forward and have something where you look back years later that you’re proud of and that it says something, and that it represents the tone of what the movie is.

And this was even done with the Egyptian instruments. I had them in the room at Abbey Road, playing with the rest of the orchestra. Of course, if one of those instruments plays off it ruins the take, you know, so there’s always the question “why don’t you just track that on another day? Just do that in a small studio, you don’t need Abbey Road for that.” I thought, no, I would rather take that risk because I think of everyone relying on each other and listening to each other… my analogy would be, if you were recording a jazz trio record you really wouldn’t want to record the upright bass one day and the piano on another! The studio and Alex, and also Tom Cruise, who is very musical himself, got behind the vision and we were able to record it properly and I’m glad we did it that way. I didn’t want to date the movie, being that this was something that involved a bigger world and however people accept the movie, or don’t, or however it goes down, you want to put your best foot forward and have something where you look back years later that you’re proud of and that it says something, and that it represents the tone of what the movie is.

Q: It’s an interesting touchstone with the Dietrich score, which you mentioned, because not only is the 1932 MUMMY the direct progenitor of this movie, but that was also the very first Universal film to have a full score, and not just main title music.

Brian Tyler: Right. That movie was a historic moment, and I think the fact is we’re talking about a score that came from the very early era of scoring – you’re only at a short distance away from scores being a piano player or an organist in the theater. Our roots as film composers being piano players in the room in a theater is kind of cool, because in that way we’re speaking for the film and the history is that we spoke for the film even before there was dialog in the film!

Q: I understand you’ve recorded over two hours of music for orchestra and choir, yet the film is only 107 minutes long. What led to that prodigious amount of music, and once it was recorded how was it pared down and assembled into the soundtrack that’s actually heard in the film?

Brian Tyler: It was interesting. The film, as it was being done, there were so many ways you could go with the movie itself, and I’ve been writing music for the film since late 2015. We really wanted to cover our bases, because it is the Dark Universe genesis, so I was taking care to write music that could work for extra scenes, and there were also scenes that, because of the running time, weren’t used in the film. When it came down to it, the whole thing was really written as a piece; it was written a certain way and we wanted the music to breathe in its natural way and have that relationship with the film. The music that was recorded actually represents the film and its overall storyline best, much in the way of it being almost like an overture or a symphony that supports the story. So we decided to include the music that didn’t make it in the film on the soundtrack album. The album, if I’m not mistaken, is 126 minutes. I think it would have been a shame not to include some of that extra music, there were such beautiful performances by the Philharmonia of London and the choir, so I’m really happy that, for once, we’re able to get it all out there.

Q: How would you describe the thematic architecture of your MUMMY score, and how challenging was it to pre-plan and map it all out?

Brian Tyler: This film is something that has very distinct themes and more than normal! It basically breaks down like this: there are a number of character themes and mood themes. You have Nick’s theme, Tom Cruise’s character; he’s kind of a rogue, a guy who has to have both adventure and also a bit of redemption built into him, and I tried to convey that in his theme. Then you have Ahmanet, which is the

Mummy theme – it has a dark and sinister aspect to it but also has a beauty and lyricism to it. The Secret of The Mummy Theme is the supernatural theme, and it most often reflects the mythology of Egypt with its own distinct melody, which is heard throughout the film quite a lot. We also have the theme for Jennifer, which is really Jennifer and Nick, as well; it’s a very melancholy theme, kind of a folk melody that is often played on the duduk, sometimes on the strings and piano and vibraphone, and it has somewhat of a sadness to it but also a kind of romantic feel. You have Set’s theme, which basically is the character of Satan, and this is the darkest theme of the score and it is a theme that kind of overtakes the Mummy and is used for any type of zombie or undead character we me et. Then you have Prodigium, which is the world of the monsters, and this is where Dr. Jekyll figures in because he is very connected to it. Dr. Jekyll has his own separate theme which is a waltz, and it’s very British. Sometimes it’s on the cello, sometimes it’s the celeste and the harp, and it’s very long-lined. Now, coming up with a Mr. Hyde theme was a trick; we already have the Ahmanet theme, which is sinister; we have Set, which is really dark and evil, so where are we going to go with Mr. Hyde? Well, instead of doing a completely new theme, Hyde’s theme is actually Dr. Jekyll’s theme played backwards! There are motifs and other bits in the movie, but basically those are the themes. Any one of those could have been a main theme for a movie, in terms of my process; usually you have one main theme for a movie with a couple submotifs, but I had full themes with A-section, B-section, C-section. It was almost like scoring seven movies! That’s why there are these pieces on the soundtrack album, called “Theme” or “Suite” or like “Secret of the Mummy” or “Nick’s Theme.” I would arrange these full suites that are not necessarily scoring particular scenes in the movie [although those themes are used throughout the film]. The first track on the soundtrack, “The Mummy,” wasn’t written to picture; that was just a recording of a theme, but it ended up actually being the Main Title.

Q: With some of these themes, have you been setting the ground work for material that will be utilized later, by yourself or by other composers, in other films in the Dark Universe? There are characters in THE MUMMY, for example, which are slated to turn up in later films in the series.

Brian Tyler: Any time you’re setting music to characters who will live on – it’s that responsibility factor you were asking about earlier – you just want to make sure that it’s in good hands and you’ve set the table with themes that can be expanded upon and solidified in a universe where you’re connecting dots with a narrative. It certainly created a bedrock that is an emotional shorthand for when you go and see another film that is in this universe and something occurs that you have experienced and whether you have taken note of what the music does there or not, I think it is important to do. It’s something that I don’t think has necessarily been done enough in film series.

Q: It certainly lends a chronological coherence to the ongoing narrative, like you did with THE AVENGERS AGE OF ULTRON, bringing in the Captain America Theme by Alan Silvestri, and things like that.

Brian Tyler: That was very much the case. As I was writing those movies there were so many new characters, and whether or not the character ended or continued, you really wanted to set that up because you really don’t know where the series is going to go when you’re doing it. This has been the same thing with NOW YOU SEE ME, and FAST AND FURIOUS. Anything that has this franchised potential.

Q: The bulk of this film feels like it’s a fantasy-adventure, but there are clearly some moments of horror in the film. How did you treat those scary moments, musically?

Brian Tyler: When I would turn on those moments, and there’s a particular sequence that I really liked and had a classic horror vibe, where the police are examining the wreckage of a plane. It’s very tense and it is straight up horror. I found that going smaller was scarier. I used a cello trio and a violin and a viola, kind of a quintet vibe, for some of that, and there’s this close, kind of a chamber sound that’s, when you’re used to the smoother, lusher sound of a 90-piece orchestra playing and then all of a sudden you have this smaller ensemble that’s turned up even more loudly and then played quietly at times with tension interspersed, it’s a really unsettling sound. You hear the rosin of the bow, you don’t have reverb… and instead of piling sounds on and getting louder and louder for intensity, it was not so much a question of loudness, it was a question of size and smoothness. I felt that by going with less instruments it was less smooth and scarier.

Q: The music kind of creeps down your spine rather than surges over you.

Brian Tyler: Right. It’s not a wash of lush orchestra. But large orchestra can be terrifying, too, I mean, listen to Penderecki, for example. But for this I felt the contrast just made it especially effective. There’s also large gaps in the music; it goes silent for a time, and then there’s weird effects, Iike plucking on the strings instead of bowing them, and there are some really dissonant things in there that are very, very quiet in the background, that are played also by only one or two instruments.

Back Lot Music has released Brian Tyler’s score to THE MUMMY digitally, with a CD to follow at an unspecified date. Listen to samples of buy the digital album at iTunes here

If you’re on Facebook, watch a video of Brian Tyler conducting the track “Egypt’s Next Queen” at Abbey Road Studios with the Philharmonia Orchestra, here.

Related story: A Glimpse Into Universal’s Dark Universe