January 3, 2019

Frankenstein 1910: Donald Sosin’s Music for Restored Classics From the Silent Film Era

Interview by Randall D. Larson

Preface

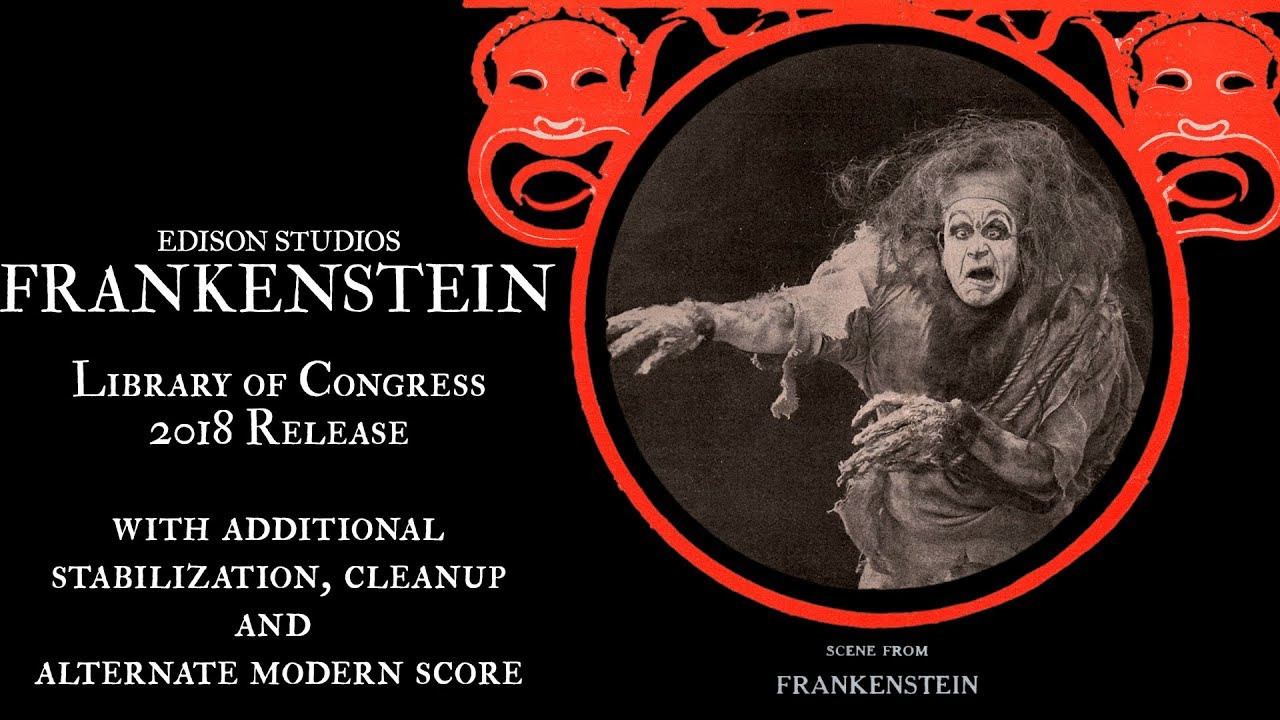

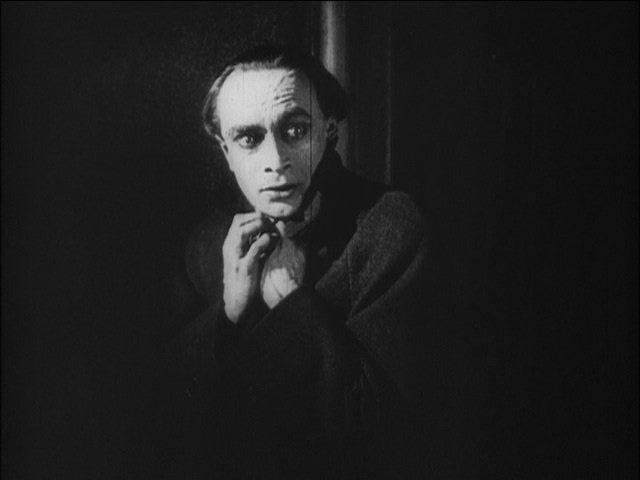

Last November the U.S. Library of Congress reported that it had made a restoration of the first film adaptation of the classic Mary Shelley story, Frankenstein. Those unfamiliar with photos in early editions of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine of actor Charles Ogle in an explosive hairdo and a Quasimodo humpback as the monster in the Edison Company’s 13-minute 1910 silent film version of Shelley’s story may be forgiven for presuming that the revered 1931 Universal Films version of the story, featuring Boris Karloff as the monster, was the first cinematic rendering of young Mary’s Modern Prometheus and his scientific progeny. It was in fact the Edison silent version of 1910 which first brought Mary’s monster to cinematic life. And then it disappeared.

The discovery of the one-reel film turned up in a collection of nitrate prints acquired in the 1950s by silent movie collector Alois F. Dettlaff, who apparently held the only extent print of the film, which he proudly carried to horror film conventions for special showings. He wasn’t interested in bestowing his prized print to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences when they asked to be allowed to preserve and archive it in 1986, but he did make a DVD out of it, which prompted all manner of youtube members to post the long-out-of-copyright film on the free-for-all video site. Dettlaff died in 2005, and nine years later the Library of Congress, having become aware of his silent film collection, purchased the entire collection. This allowed them to create a digital restoration of the film, completed with celebration in 2018 – and in a finer visual presentation than it had previously been seen – well, since 1910, at any rate.

The film’s front credits and first intertitle were missing, but the Edison Historic Site in New Jersey had a copy of the front end credit which the Library was able to drop into place and the intertitle was recreated using the style of the other title cards. The Library then asked Donald Sosin, a highly regarded silent film composer and accompanist, to provide a score to complete the restoration of the unique film.

And this is all a roundabout way of introducing to you to Donald Sosin. Reading about the LoC’s restoration of a film I had long known about – thanks to photos in Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine – and had seen the DVD version sprung from Dettlaff’s print (and read all about it in Frederick C. Wiebel’s informative 2010 book, Edison’s Frankenstein from Bear Manor Media) – I was eager to see the Library’s refurbished and scored version. That reminded me of Sosin’s history in composing new scores for scores of silent films issued on DVD and Blu-ray, which prompted me to get in touch with Mr. Sosin and arrange for the interview which follows, which covers in detail his work creating music for silent films both familiar and perhaps not so familiar, in multiple genres whether featuring monsters or comedians or just ordinary folk in compelling situations. I’ll let Sosin explain the rest – but I believe you may find his story as unique and fascinating as I have, whether you’ve seen these creative and imaginative early treatments of silent movie monsters or not. And perhaps reading of them might motivate you to seek some of them out for a welcome viewing. – rdl

Q: How did you first begin scoring restorations of silent films?

Donald Sosin: I was a student in Ann Arbor University of Michigan and had a chance to play for THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA in a campus screening, and that went well. Then I met William Perry who was doing the music for the silents on PBS – I wrote him a fan letter, we got together when I was back in New York and we became friends. He was also the pianist at MoMA [Metropolitan Museum of Art], so I started subbing for him in 1973 and when he left in the late ‘70s I was the next in line

Q: A number of the silent films you’ve scored, which is mostly what we’re discussing today, have been in the classic horror vein. A silent “horror” film of course is a far different animal in tone and treatment from what we know today in the genre. What kind of music have you found most useful when accompanying the spooky/scary/horrific moments in silent films?

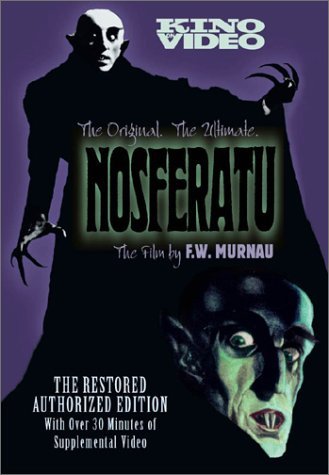

Donald Sosin: A lot of these horror films also have this pathos in them, when you think about Lon Chaney at the organ in THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA and how sad he is that Christine doesn’t want to have anything to do with him, and Orlac who has this lovely wife who doesn’t know what to do with him and his paranoid fantasies of being persecuted by this guy who turns out to be a con artist. CALIGARI is another matter, of course, but there also is this love element, somewhat warped though it is. So all of these films have a mixture of true horror and maybe some romance or some more subdued emotional content that flows in and out. It sometimes depends on the period of the film; NOSFERATU takes place in the early 1800s in Germany and in Transylvania, so in that film I’m using music that might have been part of the soundscape in both of those countries and that time period. But then there’s also the element of shock and horror, as when Count Orlok wakes up and comes up to Hutter’s bedroom to feed on him in NOSFERATU, same at the end of the film when he’s feeding on Ellen.

CALIGARI is a world unto itself – it’s just a madman telling the story even though we don’t know that, but everything is skewed within his mindset, and certainly the cinematography and the famous sets and costumes reflect that, so the music for that, in my mind, was always going to be a little weird and based more in the time period of when the film was made rather than where the film is set. I’m thinking about who was writing music in Germany in 1919, so there’s this kind of expressionistic Schönberg/Kurt Weill/Berg/Hindemith, all of those guys – I have their sounds in my ears all the time when I’m writing music for German films. WARNING SHADOWS is another case…

Q: Your score for Kino’s NOSFERATU DVD in 2002 is an especially powerful and provocative score in an orchestral style – I’m assuming this was a theater type organ you used to perform it?

Donald Sosin: No it was all synthesized. I play theatre organ but I don’t have one, and when I record over the years I’ve been adding to my arsenal of synthesizers and digital samples. And then my wife was also singing or doing vocal sound effects on that film.

Q: Yes, I very much like the voicings provided by Joanna Seaton. I love how she gave life to Ellen with her gasps! You also provided some effective themes than run throughout the score, as well as a compelling pan-flute-ish motif.

Donald Sosin: Yeah, I have a friend from Romania who is really a terrific pan flutist and I got to listen to him play live a number of times.

Q: What can you tell me about composing this score and capturing many of its classic moments in a fresh musical way?

Donald Sosin: We did NOSFERATU live a couple of weeks ago. I used some of the same themes but I’m always looking back and thinking, “well, was that the right choice?” I’m thinking for the long shots when Orlok has loaded is coffins into the ship and there are going to the port, I’m thinking I made a wrong choice with the sort of CAPTAIN BLOOD music I used for the Kino recording. The music for that scene is more like MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY, and I think now it should probably be something more slow and scary. But it’s what I was thinking about at the time, and then I alternated that with Hutter going through the mountains leading his horse and then coming back. But there are so many different ways to do this and so many different people scoring silent films, there’s never one right way to do it. It’s a nice feature of this weird art form that you get to do it different times, maybe, and change your mind about what’s going on.

I’m in the process of doing a two-hour film called THE ANCIENT LAW, and the violinist Alicia Svigals and I scored it a year ago for Flicker Alley DVD, and we’ve done about ten performances and it’s always different. We’ve kept about 60% of what we did, which is notated, and then the other 35-40% we’re just improvising in our performances, as our ideas about the film develop. It’s more fun for us, also, in a live performance experience to just be able to react freshly to the film rather than chaining ourselves to looking at a printed score for two hours. When I wrote a new score in the fall of 2017 for CALIGARI, which I had scored for Kino in 2001/02 something like that, I used a lot of that music but then I rewrote a lot of it, too. I also wrote everything out for the instrumental and choral ensemble, so we were slaves to a click track for the entire time so that everything would be in sync.

Q: In 2013 you composed a score for the German language version of HANDS OF ORLAC, which premiered in Austria, with Dennis James playing the Rieger organ and yourself on piano. I really like the sound of that, especially the mix of the organ and the piano together and the way you configured that. What were some of your thoughts as you were composing and developing that score?

Donald Sosin: That project was the idea of Dennis James, a great theater organist. I think he had a relationship with the Konzerthaus Vienna and they do something like four silent films of live music every year, so they specifically wanted something for organ and piano. That can be a pretty difficult ensemble to write for, because the organ can be so overwhelming over the piano. I had to be very careful in writing that I wouldn’t overpower myself and could work out something where we could keep together; we had a click-track but it wasn’t always functioning the way I wanted it to, so it was a difficult event to bring off. I liked some of the music that I came up with and then other things like the whole scene leading up to the crash of the train I think I would completely do differently now.

Q: You also directed a live improv score for NOSFERATU in 2011 featuring UC Denver music students. How did this presentation come about and how did you and the students treat the film to an improvised accompaniment for piano, chamber group, and voices?

Donald Sosin: We had two-and-a-half, three days to sit and watch the film together and make up themes and then use them as a springboard for our live improv. I guess you can say it was all improvised but there were themes that had been worked out in advance.

Q: What a great opportunity for the students!

Donald Sosin: Yes, it was! We’ve done that about six or seven times with different films in Denver. We’ve done CALIGARI, Lon Chaney’s THE UNHOLY THREE, and we’ve also done non-horror film like BERLIN: SYMPHONY OF A CITY, so they’re really interested in that process. We’ve had some great experiences.

Q: You’ve composed music for CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI on three separate occasions, the most recent being for the Syracuse Film Festival in 2017. What brought that about and how would you describe the differences in how you approached scoring this film, and had opportunities to update things you wanted to change from your early CALIGARI accompaniments?

Donald Sosin: Actually it’s more than three now, it might be as many as ten! I first played for it in Michigan in the ‘70s, and I even have a notebook – I keep many notebooks of themes that I sketch or longer musical ideas that I use for films – so I’ve kept the themes that I wrote for CALIGARI back in 1971-72, and then when Kino asked me to do it, I was able to use the music which has stuck with me the most for that. I sat down and watched the film in silence, as I always do, and think about what’s going to work here, and maybe turn on the recorder and start playing along with some scenes, or work on pencil and paper thinking about the music completely separately from the film while I’m puttering around the house or whatever. That Kino score was the one I was referencing for the next fifteen years. And then I met the people than run the Syracuse International Film Festival, through mutual friends, and they said “we always have a silent film on our program, and would you like to do CALIGARI?” And I thought, “Oh, again?”

But it was fun. I had great professional musicians in Syracuse to work with as well as the Colgate University Chamber Choir. Originally I had asked for just a group of actors who could vocalize some things, but I was given singers to work with so that changed my conception of what the vocal element was going to be. We had them do some vocal sounds, like crowd noises, and one of them was playing a bass drum. My wife did all the teaching of that material in our sessions, although the chorus was prepared by their director, who unfortunately couldn’t be there for our final rehearsals and the performance due to a family emergency. So I didn’t have much time to think about what the chorus was going to do, so a lot of the choral music was doubling what the instruments were doing. I believe all of that was completely scored with a click track. It worked out pretty well. I would love another chance to do that or to record the score; some good music came out of that time.

Q: Unlike scoring a modern feature film where you have cues, here you’re scoring and playing as much as two hours of nearly constant music, going on all the time. How challenging is that to conceive and then to perform in a live situation?

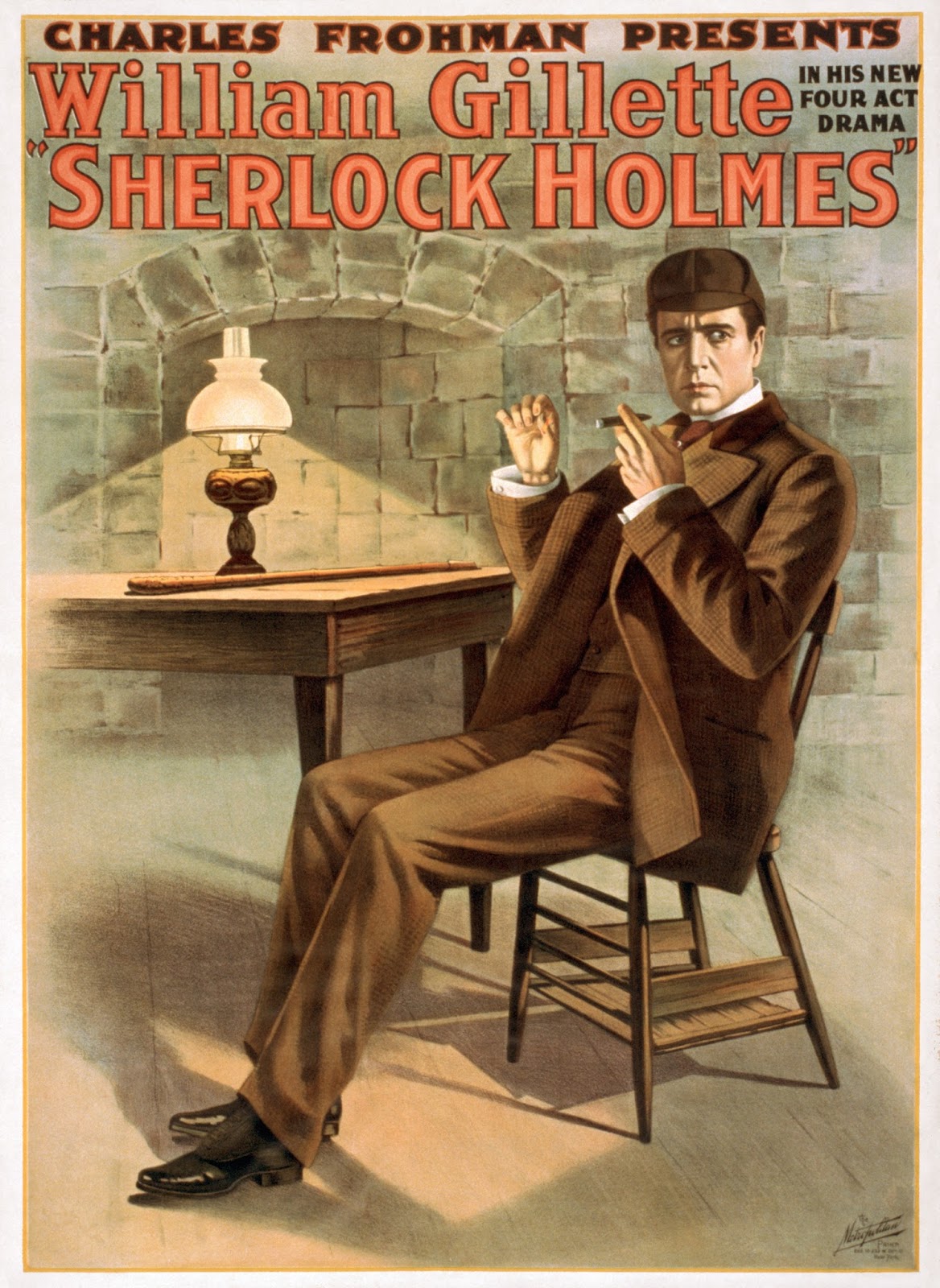

Donald Sosin: I think the longest film that I’ve actually scored was about two hours, the 1916 SHERLOCK HOLMES with William Gillette. That’s a lot of work! And in Hollywood they have lots of people working on all this stuff – for example, if you’re Hans Zimmer you’ve got lots of composers and orchestrators working with you. I wrote every note of the piano reduction for SHERLOCK and then farmed out all of the orchestrations, with very few exceptions, to my friend the very gifted Peter Breiner, who’s a very formidable composer/arranger/conductor/ pianist. He did the orchestration really wonderfully. But SHERLOCK wasn’t by far the longest film that I’ve ever played for. Some of the films that I sit down and play for are three or four hours long – like Henri Fescourt’s MONTE CRISTO [1929], three hours and 45 minutes; JOYLESS STREET [1925] and GÖSTA BERLINGS SAGA [1924] are each three hours long, LOVE AND BEAUTY is over three hours, and LES VAMPIRES the French serial by Louis Feuillade is seven hours and nobody does that without a couple of breaks. You have to have, as my friend Bill Perry said, Wagnerian sitzfleisch – you have to be able to sit there for a long time and have a constant flow of creative ideas, even if you have themes written down. Sometimes for a three-hour film I’ll just have two pages of music, if that, written out for the characters, and so the rest of it is just totally watching the film and playing and improvising as I go along. For that I am very fortunate that I learned Transcendental Meditation in college because this gives me a daily dive into a vast ocean of creativity.

Donald Sosin: I think the longest film that I’ve actually scored was about two hours, the 1916 SHERLOCK HOLMES with William Gillette. That’s a lot of work! And in Hollywood they have lots of people working on all this stuff – for example, if you’re Hans Zimmer you’ve got lots of composers and orchestrators working with you. I wrote every note of the piano reduction for SHERLOCK and then farmed out all of the orchestrations, with very few exceptions, to my friend the very gifted Peter Breiner, who’s a very formidable composer/arranger/conductor/ pianist. He did the orchestration really wonderfully. But SHERLOCK wasn’t by far the longest film that I’ve ever played for. Some of the films that I sit down and play for are three or four hours long – like Henri Fescourt’s MONTE CRISTO [1929], three hours and 45 minutes; JOYLESS STREET [1925] and GÖSTA BERLINGS SAGA [1924] are each three hours long, LOVE AND BEAUTY is over three hours, and LES VAMPIRES the French serial by Louis Feuillade is seven hours and nobody does that without a couple of breaks. You have to have, as my friend Bill Perry said, Wagnerian sitzfleisch – you have to be able to sit there for a long time and have a constant flow of creative ideas, even if you have themes written down. Sometimes for a three-hour film I’ll just have two pages of music, if that, written out for the characters, and so the rest of it is just totally watching the film and playing and improvising as I go along. For that I am very fortunate that I learned Transcendental Meditation in college because this gives me a daily dive into a vast ocean of creativity.

Q: Your most recent score was a much shorter effort – the 13-minute restored version of Edison’s 1910 FRANKENSTEIN for the Library of Congress. This was a solo piano score – would you describe how you developed the music and performed it to sync with the film’s ambitious moments of drama, science fiction, and horror?

Donald Sosin: That sounds like a well thought-out question – I wish the music were that well thought out! George Willeman at the Library of Congress sent me the files and I watched the film. What I do, initially, is put it into a sequencer – I use Digital Performer with all of the films that I’ve scored, and this one’s no exception. I just put bookmarks or markers into the sequencer so I know exactly where the next shot or the next event falls that I feel is of significance, and then I know how many seconds I have in between each cue. I don’t always think of it in terms of “cue” – the longer episodes, yes, but individual ones I’m just watching the film and I’m composing as I go along. Since this film was short, I think I played for it three or four times and then I chose from those different takes different sections and cut and pasted them together to make a final version. I wrote a theme for Frankenstein ahead of time and used that throughout the film.

Donald Sosin: That sounds like a well thought-out question – I wish the music were that well thought out! George Willeman at the Library of Congress sent me the files and I watched the film. What I do, initially, is put it into a sequencer – I use Digital Performer with all of the films that I’ve scored, and this one’s no exception. I just put bookmarks or markers into the sequencer so I know exactly where the next shot or the next event falls that I feel is of significance, and then I know how many seconds I have in between each cue. I don’t always think of it in terms of “cue” – the longer episodes, yes, but individual ones I’m just watching the film and I’m composing as I go along. Since this film was short, I think I played for it three or four times and then I chose from those different takes different sections and cut and pasted them together to make a final version. I wrote a theme for Frankenstein ahead of time and used that throughout the film.

Q: The film is interesting being among the annals of early horror and the first such film about the monster that would later become a horror icon. As a whole in scoring some of these it must be fulfilling to have a part in the restoration of some of these classic American and European silent films from cinema’s earliest days. Had you been a fan of silent cinema when you started scoring these films?

Donald Sosin: When I started I didn’t know anything about silent film other than having seen FRACTURED FLICKERS with Hans Conried on TV! And so my first exposure to PHANTOM OF THE OPERA and BIRTH OF A NATION and then INTOLERANCE and all these others Griffith films, along with William S. Hart and Langdon and Lloyd and Keaton, it was totally new to me. I was very fortunate to have a mentor in Michigan who was a film professor in the Engineering School, Hubert Cohen – and he’s still there teaching, forty years later –who sat me down with 16mm prints of all these films ahead of time and said “Look at this! Look at this! Look how these shots are created and look how the editing is on this…” So he was my guide through a lot of these early films and that’s where I started thinking “Oh, this is really something amazing!” Then over the years I’ve met so many people who are either academics or involved in film restoration or write about these films and then I play in Pordenone and Bologna and listen to people talk about it, so it’s become the major focus of my career, working and thinking about silent film, which was not ever my intention when I started out. I thought I was going to go to New York and write Broadway shows or whatever! But here, 47 years later, with 60 some DVDs and my wife and I go all over the world doing live performances and teaching younger musicians how to write silent film music, it’s pretty much a full time career.

Q: Being on the cutting edge on our legacy in cinema, reviving these and bringing them to the interest of people who might not be aware of them, sounds like a really great thing to be devoting yourself to.

Donald Sosin: We do, actually, Joanna and I, think of ourselves as sort of evangelists in the world of silent film. I’m very keenly aware that there is a tiny, tiny minority of people alive today who have ever seen any silent films, with or without live music, and we often make that point when we’re doing our performances. So we’re always trying to raise the flag and get people to come out to screenings when they can.

For more information about Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton and their work with silent films, see here.

For information about the U.S. Library of Congress Silent Film Database and film restoration project, see here.

For more information about the LOC’s restoration of the 1910 FRANKENSTEIN – and to watch the restored film online – see here.