Interview: Christopher Young

Scoring a Chinese Historical Fantasy Epic

Interview by Randall D. Larson

September 13, 2019

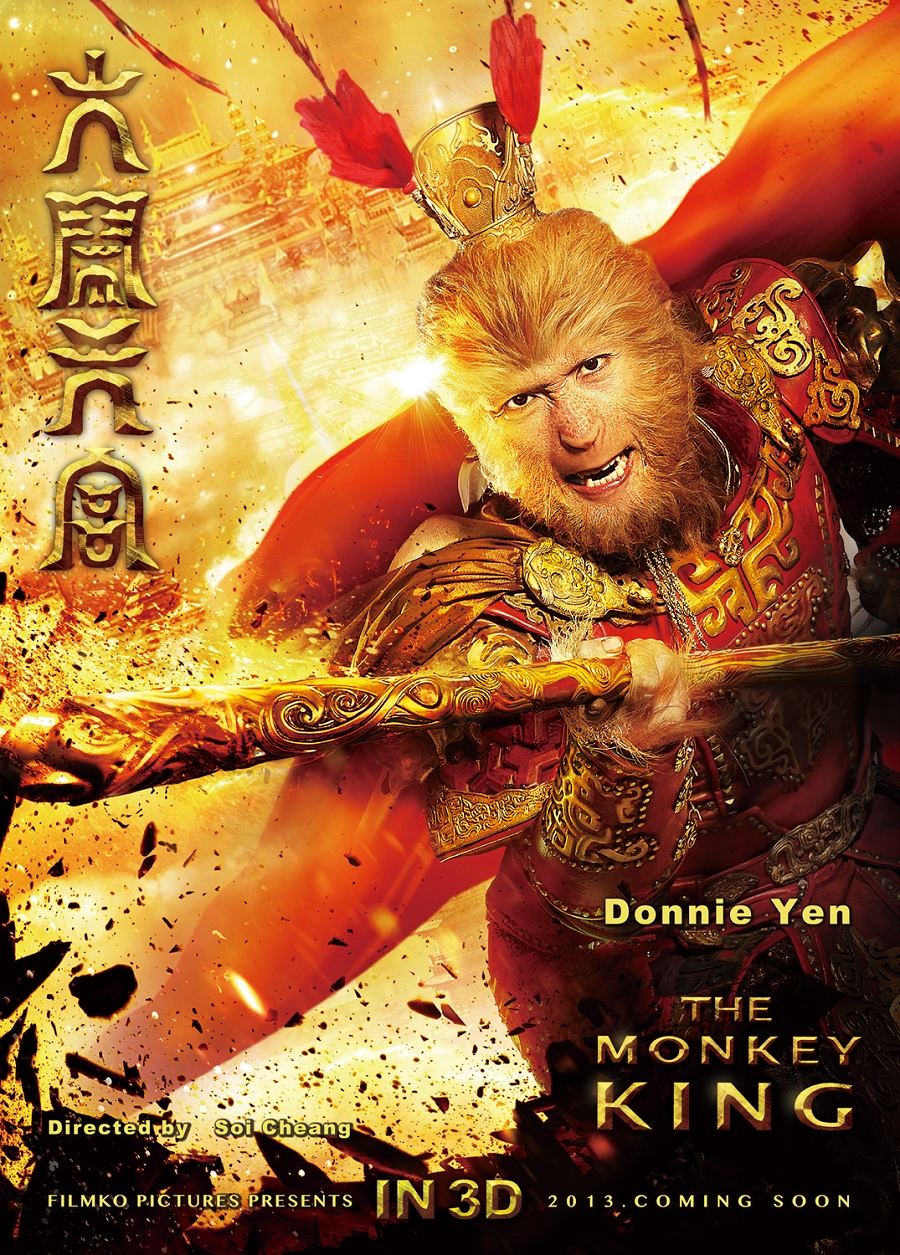

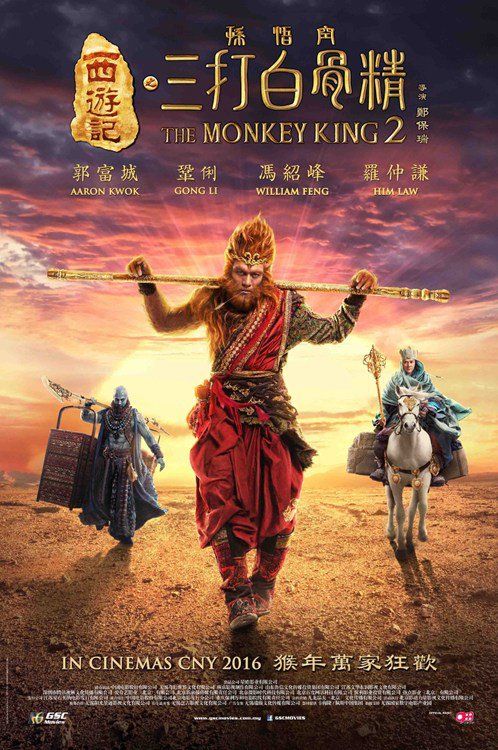

THE MONKEY KING is a 2014 Hong Kong/Chinese action-fantasy film series filmed in 3D, directed by Cheang Pou-soi and starring Donnie Yen (who also served as the film’s action director), Chow Yun Fat, and Aaron Kwok. The plot is based on an episode of Journey to the West, a Chinese literary classic written in the Ming Dynasty by Wu Cheng’en, and considered one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. It has been filmed many times; most notably as a four-movie Hong Kong film series produced by the Shaw Brothers Studio (1966-68: MONKEY GOES WEST, PRINCESS IRON FAN, CAVE OF THE SILKEN WEB, and THE LAND OF MANY PERFUMES), A CHINESE ODYSSEY, a two-part 1995 Hong Kong fantasy comedy starring Stephen Chow (and its 2017 sequel, JOURNEY TO THE WEST: THE DEMONS STRIKE BACK), THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM, a 2008 Chinese-American fantasy-adventure martial arts film featuring Jet Li as the Monkey King, and many more.

The first of Pou-soi’s ambitious three-film adaptation (released in Asia in 2014, 2016, and 2018) received mixed reviews but broke numerous box-office records in China. THE MONKEY KING 2 received better reviews, with THE MONKEY KING 3 hitting a foul ball back to mixed reviews. All three films feature extensive CGI, with special makeup effects supervised by Hollywood veteran Shaun Smith. Composer Christopher Young (HELLRAISER, SPECIES, SPIDER-MAN 3, SWORDFISH, THE SHIPPING NEWS, 2019’s PET SEMATARY,), composed the score for the first two MONKEY KING movies, but not the third. Young’s soundtracks for the first two films were both released by Intrada Records (the label is currently sold out).

The following interviews with Young were made in March 2017 and December 2018 and are published here for the first time.

Q: How did you get involved with THE MONKEY KING movie?

Christopher Young: THE MONKEY KING movies were not in fact ones that I chased down. It was actually Paul Talkington, who’s a fan of my stuff and he’s been my orchestra contractor whenever I go overseas, which is where I often go these days when I’m recording orchestra. He heard about this and in conversations with them he suggested that I might be the perfect person to score these movies. They’d been looking for a Hollywood composer who’d been around the block a bit, and so it was he who actually made the connection—so I’m forever indebted to him. Little did I know that it was something that was going to consume two years of my life! But what was wonderful about this was that the type of scoring which has become passé in film scoring over here—I’m going to call it the “old school way of thinking about film music”— apparently in China that school is something they adore. They wanted a big orchestra and lots of melody!

Q: It’s such a thick, epic sounding, lush group of melodies and harmonies. When you began scoring the first film, how did you come up with the musical approach?

Christopher Young: They gave me the green light to think big. In terms of the nature of the story, I did some research on it and I got an English translation of the book it’s based on, but I didn’t get through much it. I’m going to have to tell you, I still to this day I don’t really understand the story entirely! When I began working on it you can image that what you see now, when you look at MONKEY KING—less so MONKEY KING 2—was at that time just a bunch of blue screen: a wall of blue backing with the actors hanging from wires, and I was told this is going to be China Heaven in the clouds, or something. You never know how that kind of film falls into place, but in this instance I’m particularly amazed that it did fall into place, for two reasons. One is what I just mentioned, visually. In the opening, the only areas where there was really any kind of special effect visuals developed enough so I could kind of get a sense of what was going on was the beginning. The rest of it wasn’t finished yet, it was just actors dangling on wires in front of a blue screen. They had to describe to me what was going on.

The other reason was, of course, that the filmmakers spoke Chinese. They had printed subtitles so I could understand what the actors were saying, but the guy who translated them was not very good at translation, so that only confused the story more! Fortunately I had two assistants who knew the story well, and they could guide me. In terms of the sound, I knew I wanted to include some Asian instruments—but I didn’t go strictly Chinese. The most prevalent Chinese instrument featured in that score, and even more so in the second film, was the erhu. And that gets used in Hollywood movies all the time, so it’s not like I pulled some new color into the palette that no one had used before. I had the pipa, the Chinese classical guitar, but getting good pipa players in Los Angeles is not easy, so I relied more on the shamisen and the koto and the biwa in lieu of using purely Chinese instruments. The Japanese hichiriki, that nasally, whining oboe-y kind of thing, which I love and has such a distinctive sound, is heard in the first move.

In the first movie those instruments appear mainly as solo instruments: one shamisen, one biwa, one koto, one erhu, etc. But in the second film, I’d gone out and done some research. I actually saw some concerts here of shamisen ensembles or koto ensembles, and I thought “Wow that’s a great sound. You get 20 people in a room and they’re all playing the same thing in unison!” It had this monstrous sound! So that became the palette for the second movie.

Now, for one of the first pre-recorded things that I did, I brought in three Japanese koto players. I recorded here at my place. So I brought in three koto players, but it turned out that two of them were not doing so hot, so I immediately realized I needed to get one ace player and just multi-track him as many times as I needed. So that became the formula. With the aid of my engineer, I found out exactly the right number of overdubs we needed. Like with the shamisen , I think the magic number was six, it made the sound just right; anything less or even one more didn’t quite work as well. So we had to figure out what that magic number was, depending upon the instrument, and I then multi-tracked the players. And you have to have players who read, and of course Japanese and Chinese notation are different. You can’t get someone who doesn’t read Western notation, which I’ve done before; they have to come in, look at the score, and then they rewrite it in their notation.

Q: Did you go to China to meet with the filmmakers or did they come over here?

Christopher Young: I went over to Beijing, where the film was in post-production, and that was it. It was so unique, and in many ways a dream come true: I fly over there, I’m there for something like three days. They were struggling to get the film finished—it had been in post-production I think for two years; they had run out of money and the special effects were barely begun when I saw the cut. We spent two or three days together going through the movie. I can’t speak any Chinese; so we had someone who translated. The director spoke some English. We went through the movie and what was interesting is that, you know how it is in American fantasy films, often most of the conversation is about “oh and don’t forget we need the music to hit this and then of course it needs to change here, and yes this is a moment of happiness so make the music happy” and that kind of thing. They run down all the things that they want the music to acknowledge and parallel as the film progresses. But here, the director simply said “I want the music to start here, and this is the general feeling that I want the music to acknowledge.” And I’d say, “Do you want the music to hit anything special…?” “Oh yes, this moment here, maybe that moment,” and that was it. And so he pretty much gave me permission to just think of the film as a chance to write music in which my primary concern first and foremost was “How does this work as music? How does it hold together as a piece of music, away from the movie?” And then stylistically he wanted it to address the essence of what the scene is, and that was it.

When I came back from Beijing I began to come up with a lot of themes. Either he told me or I determined which of the main characters may need a theme, and once I had a number of themes written, the first order of business is bringing the director over here and showing him theme options for the different characters or dramatic moments. What you normally do is mock it up if it’s going to be an orchestra thing. Now with these guys, all we did was a source-connect thing, and I played on the piano—well, I had someone else play because my piano playing is terrible—and we would just play the themes. I wrote these themes in a song form and we played them for them and we’d say this would be for this character and probably this moment in the movie, something like that, and he would listen to option number 1, options 2, 3, 4, 5, however many, pick out a favorite, and we’d move on to the next one. He agreed to maybe ten primary themes or motives or ostinatos or something, and that was the last time I spoke to him before I went on the stage to record the music. No mock-ups, no checking anything, no nothing. I was entirely on my own!

Q: Wow, what a freeing kind of experience, but at the same time were you worried?

Christopher Young: I was seriously worried! What happens if he shows up and goes, “What is this?!” But they loved it. They made a few requests when we were recording, like “can you drop that French horn, there?” That was about it.

Q: How would you describe your thematic architecture for the first and then the second film?

Christopher Young: You’re asking a tough question! As you know, I was raised listening to Max Steiner, Aaron Copland, and Erich Korngold, the kings of melody, and in essence every single one of those themes in that film started as something that just popped into my head and I worked it out in standard song form, intro-A-A-B-A or something like that. Once I get a tune I look at the scene and, if they’re allowing me spell-out the tune, I will always try to do that and use that as the guide. I think that’s what probably distinguishes that score, and what makes it old school. It’s not so much the vibe but the intensity—and the density—we hear in those old, big scores. Even KING KONG had that same kind of density and intensity and Gothic grandiosity. When I’m allowed to do what I like to do the best I will do the same thing I’ve always done: start the movie off by coming up with a grab bag of themes, have the director approve the ones he prefers, and then write the main title, probably the end title, do the bookends, and then I’m off and running. I pick the primary theme first, which allows me to settle on that or present that theme, and then modify and develop them in a theme-and-variation kind of idea.

Q: Once you’ve got the main tune down at the start, what was your process of assigning instruments to them and fleshing them out into a fully harmonized structure?

Christopher Young: I don’t think it’s any different for me than it was for Max Steiner. As the theme came into his head, so did the sound. I pretty much have them worked out in my brain. The minute something comes alive inside my head, a tune or a theme, I know exactly what it’s going to sound like; I have that sound in my head. That’s part and parcel; it’s not like I write the themes at the piano and then wonder what it’s going to sound like and gradually get to the point where it becomes what it is. That’s the other great thing about the old school, up until the whole method way of composing at the synth became the way to write, every composer had to work it out in their heads.

I just did an interview with Jon Burlingame for the Academy, and that question came up: “What’s the major thing that’s changed since you moved out here in the whole film music composing process?” I said, “Well it’s the fact that you don’t have to work it out in your head anymore, because you can write and input directly into the computer and get immediate feedback; whereas even when I was doing student movies at UCLA, you sat at the table, you imagined it, you put the notes on paper, and you get scared shitless! Because you’re the only guy who knows what it’s really going to sound like in the end, and everyone’s looking at you asking “how does it sound?” “It sounds okay in my head, I think!” You bashed it out on the piano a little bit, but when they take it on the stage, everyone’s hearing it for the first time—including you! It was pretty nerve-wracking, but now everything gets mocked up. Even an orchestra score starts with a digital mock-up, and that takes a certain amount of the edge off when you go on stage, but it also allows you not to have to depend solely on what your inner-ear is telling you. So to answer your question, on both THE MONKEY KINGs, not a note of that was mocked up. Not one note! So it only existed in my head and then off it went to the orchestrators. So that was the nice thing about THE MONKEY KING—that I didn’t have to go through that phase of mocking things up. It made me able certainly to focus on the writing, and I didn’t have to worry about going downstairs and taking time off to make sure that all the demos sounded great.

Q: What kind of musical evolution went into the second film? You’ve already mentioned that you used more ensemble instruments, but in terms of your themes were you able to expand them in the second movie?

Christopher Young: The first film takes place in China Heaven, and there are these big, bombastic battle scenes in the fantasy world. The second film is earthbound, so that’s the major difference. There are moments where it gets big and bombastic during some of the fight scenes, but there’s very few scenes that I recall that are heavenly. But all they told me on the second film was “We’re most interested in your capturing the emotion.” The Monkey King has to have this experience in order to learn humility, and it’s also about the relationships between him and Tang Sanzang, the monk who is helping him, and the lesson he needs to learn through discovering compassion for someone other than himself, because he begins as a very selfish character. So that’s what they were most interested in, my writing emotional music. Then there was of course the evil woman, White Bone Demon, and finding her sound and at the same time trying to acknowledge the fact that she’s an extraordinarily beautiful woman but completely evil, and so I used the erhu for her but whacked it out a bit; it was an altered erhu. That was her sound. And as you mentioned, in the second film I used more of an ensemble of the Asian instruments, so there were very few solo ones. On the CD there are themes that I ended up recording that never made it into the movie. I just came up with so many themes, but I don’t think I really used any of the themes from the first film in the second one. Why, you might ask? I can’t really answer that question except I guess I sat down to watch the second movie, and just a whole bunch of new themes poured out.

Q: Where did you go to record the score?

Christopher Young: That was recorded in Bratislava with the Slovak National Symphony Orchestra and Lucnica Chorus. On the first film the orchestra was conducted by Nic Raine and the choir was conducted by Allan Wilson; on the second film the orchestra was conducted by Allan Wilson. I’m in love with that orchestra and they understand me really well. I’m always knocked out when I hear them play my music!

Q: What happened that you didn’t wind up scoring MONKEY KING 3?

Christopher Young: I honestly can’t tell you—I never heard a word from them during the whole process of production and post-production of MONKEY KING 3. Not one word! I sent emails to the director, saying how excited I would be to be a part of that team again, and I just never heard anything from them. They were certainly pleased with what I did for the first two scores, or that’s what they told me. I have absolutely no idea why they chose not to go with me.

For more information on the composer, see his web site at http://officialchristopheryoung.com/