Books About Fantasy/SF/Horror Films & Their Music

Notes & Reviews by Randall D. Larson

(Originally posted in Soundtrax)

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Film Music Books

James Newton Howard’s SIGNS, A Film Score Guide

James Newton Howard’s SIGNS, A Film Score Guide

By Erik Heine

Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016

210 pages, 8.5×5.5, paperback, $59 (ebook $55)

This book first came to my attention last January, and I gave it a short plug in that column, but now that I have the volume in hand, allow me to elaborate a bit more on it in this full review. James Newton Howard’s Signs, A Film Score Guide by Erik Heine is among the most recent of Rowman & Littlefield’s series of book-length film score examinations, which thus far totals 19 volumes, from 2004 to 2017. Its author is professor of music at Oklahoma City’s Wanda L. Bass School of Music, and he has written extensively on film music. Heine divides the book into six chapters: examining Howard’s musical background, his film scoring compositional process, a historical and critical examination of the film SIGNS, investigating the sounds of science fiction and director M. Night Shyamalan’s approach toward the genre, Howard’s technique of sketching and scoring SIGNS, and finally the author’s essential analysis of the SIGNS score. There are a number of musical examples for those who can read music, and a number of tables which illustrate the score’s structure and various distinctive sections within cues and in the composer’s recurring use of a three note motif in this score.

“James Newton Howard’s music for SIGNS, like many of his scores, takes a new approach for a film,” Heine writes in the book’s introduction. “The idea of basing the music on a single gesture is an approach similar to that of the early twentieth-century composer Arnold Schoenberg, but the largest influence on the score comes from Igor Stravinsky, specifically his music for the 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring… Howard’s approach to this film [is] an outlier when compared with the rest of his career. In doing so, his music for SIGNS will be recognized, not only within his work with Shyamalan, but as one of his most significant and best film scores.”

What follows is an extremely thorough and detailed analysis which will be valuable both for those musicologists and academics who can read music as well as those film music followers and examiners who don’t (in other words, don’t let the inclusion of technical musical data or samples of musical staves draw you away from this important book; there is plenty of detail and discovery in the author’s text to understand the form, function, integration, and structure of Howard’s SIGNS score.

“Despite Howard’s adeptness at composing long melodies and themes, as he did in UNBREAKABLE, he shies away from that side of his compositional abilities in SIGNS, instead favoring a dedication to the three-note motive,” Heine writes at the end of his cue-by-cue analysis of the score in Chapter 6. “Through that adherence to a minimum of compositional means, Howard created a film score that can be described as an example of minimalism… In SIGNS, Howard’s music doesn’t slowly change over time, nor are the process and the final product the same thing, but the three-note motive from the beginning develops and transforms into something wonderful.” Heine’s conclusion demonstrates just how powerful this seemingly simple score is, how it’s treatment of the three-note-motive represents various connected elements of his score, and how it delivers a profound resolve by the film’s end, as the reader will perceive.

“Howard’s score for SIGNS is one of his most effective, most inspired works,” Heine concludes in the book’s epilogue, “and will continue to affect anyone who watches the film long after the credits stop rolling.”

This book is the first to examine the composer’s work in detail, and in so doing demonstrates why and how James Newton Howard’s film music style is challenging to pigeonhole. The comprehensive analysis in this book also affords the first significantly broad examination of the music in any of Shyamalan’s films. It deserves a place in any thorough library of film and film musical studies.

– Randall D. Larson

_______________________________________________________________________________________

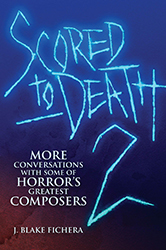

Scored to Death 2:

More Conversations with Some of Horror’s Greatest Composers

By J. Blake Fichera

Los Angeles: Silman-James Press, 2020

494 pages, 9×6, paperback, $24.95

www.silmanjamespress.com

In the sequel to J. Blake Fichera’s popular 2016 first volume, Scored to Death 2 offers a much welcome compendium of new interviews with 16 more film composers who have specialized in or made significant contributions to horror film music. The second book is larger by more than 100 pages than the first, containing fascinating and in-depth interviews with such horror score notables as Richard Band, Charlie Clouser, Michael Abels, Joseph LoDuca, Koji Endo, Brad Fiedel, Bear McCreary, Craig Safan, Holly Amber Church, Kenji Kawai, and many others, offering a provocative and quite fascinating journey into the making of music for this broadly specialized form of filmmaking. As a musician and film editor, Fichera knows the kind of questions to ask that will prompt memories and generate comprehensive discussions, illuminating not only the menacing musical mores of scare cinema, but in-depth details about the horror scores these ladies and gentlemen of the baton and/or the battery of electronica have created. From classics of a few decades back like CREEPSHOW, RE-ANIMATOR, DAY OF THE DEAD, DARK SHADOWS, THE TERMINATOR, to more recent chillers like GET OUT, IT FOLLOWS, SADAKO VS. KAYAKO, HAPPY DEATH DAY, GRETEL & HANSEL, DEATH NOTE, and much more, Fichera asks provocative questions that stimulate comprehensive answers.

The horror genre is booming these days, and has grown into a multiplicity of categorical sub-genres; with this growth, composers and musicians around the world have found new styles and innovations in musical sound that expands the immersive experience of watching scary movies. Scored to Death 2 follows on the popularity of Fichera’s first volume by providing an ongoing conversational examination about the art and science of fright films which is both intriguing and instructive. It will answer questions about the how and why behind some of the most powerful and affecting scare scores of recent decades, which will educate and enlighten fans and followers of these films while also offering insights and inspiration for those seeking to follow in the haunted footsteps of these music makers into the horrific halls of fearful film scoring.

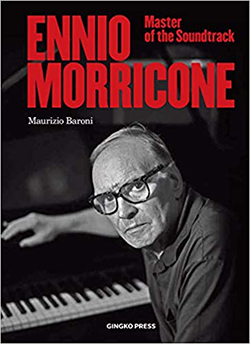

Ennio Morricone Master of the Soundtrack

Ennio Morricone Master of the Soundtrack

Maurizio Baroni, Texts by Germano Barban

Gingko press, Hardcover, October 2019

368 pages, 8 2/3” x 12”, $69.95

Website here

This large, thick hardback is the first major work dedicated entirely to the discography of the maestro Ennio Morricone. Unique in its genre, Ennio Morricone: Master of the Soundtrack originates from the idea of the collector, author, and cinema expert Maurizio Baroni, who draws on his own archive to give life to a rich selection highlighting over fifty years of a prestigious career, largely unseen before, which includes handwritten scores by the maestro himself, the original album and single cover sleeves from his soundtracks, and much more.

In addition to Baroni’s exhaustive capsule comments on Morricone’s soundtracks, each accompanied by examples of album artwork, he has accomplished getting twenty single- or half-page thoughts of the Maestro from a variety of filmmakers from Dario Argento, John Boorman, Quentin Tarantino, Giuseppe Tornatore, Liliana Cavani, and John Carpenter to singers such as Edda Dell’Orso and Gino Paoli, actors like Lisa Gastoni and Franco Nero, composers like Nicola Piovani and Daniele Furlati, and others—each covering a unique aspect of Morricone they especially admire or have witnessed. A myriad of full color images run throughout the book to accompany each of the pages that cover individual recordings, and can be also accessed via an index at the back of the book; entries are sorted chronologically and separated into decades from 1961 through 2016. Baroni doesn’t attempt to list every individual edition of each of Morricone’s soundtracks (something H.J. de Boer and Martin van Wouw attempted quite exhaustively with The Ennio Morricone Musicography in 1990, and something the website soundtrackcollector.com continues to provide, for all film soundtracks). What Baroni has compiled and focused on is a useful, accessible, and annotated illustrated discography of Morricone’s recorded musical output. The result is admirable as a reference source and a browse-as-needed guide seeking an overview of the composer’s musical output.

This thick, heavy, and oversize book serves as both a tribute to the late composer (he was still alive when the book was published, and reviewed a draft with enthusiasm), and an overview with commentary of his prodigious discography of his soundtrack work. The book focuses on providing the reader with a hefty illustrated guide that provides a welcome abundance of perusable material to enjoy, study, or find what’s needed to try and fill gaps in one’s own Morricone soundtrack collection. Pouring over it becomes an enthralling opportunity to admire the composer anew and examine the art design of record sleeves over a 55-year period, and recollect the magnificent music houses within those cardboard or paper sleeves.

Music by Max Steiner –

The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer

Steven C. Smith

Oxford University Press, Hardcover, 2020

496 Pages | 109 photos, 18 illustrations. $34.95

Website here

During a seven-decade career that spanned from 19th century Vienna to 1920s Broadway to the golden age of Hollywood, three-time Academy Award winner Max Steiner did more than any other composer to introduce and establish the language of film music. Indeed, revered contemporary film composers like John Williams and Danny Elfman use the same techniques that Steiner himself perfected in his iconic work for such classics as CASABLANCA, KING KONG, GONE WITH THE WIND, THE SEARCHERS, NOW, VOYAGER, the Astaire-Rogers musicals, and over 200 other titles. And Steiner’s private life was a drama all its own. Born into a legendary Austrian theatrical dynasty, he became one of Hollywood’s top-paid composers. But he was also constantly in debt–the inevitable result of gambling, financial mismanagement, four marriages, and the actions of his emotionally troubled son. [-from the publisher’s website]

Steven C. Smith is the author of A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann (1991) and is a four-time Emmy nominated journalist, writer, and producer of over 200 documentaries about music and cinema. His thoroughly researched biography of Max Steiner is divided into five parts, covering in detail:

- Where Steiner came from (“Part One: The Little Prince” – chapters 1-2)

- What brought him to the USA via London from his native Austria (“Part Two: The Wanderer” –chapters 3-5)

- What brought him to Hollywood via Broadway and how the arrival of David O. Selznick and Steiner’s scoring of SYMPHONY OF SIX MILLION (1932) set the stage for everything that would follow in film music and Steiner’s major part thereof (Part Three: “The Apprentice” – chapters 6-10; chapter 8 covers KING KONG in great detail and the part Steiner’s music played in its success; Chapter 9 covers working on the debut Astaire/Rogers musical FLYING DOWN TO RIO; Chapter 10 covers John Ford’s THE LOST PATROL, which earned Steiner his first Oscar nomination for music)

- Steiner’s mastery of film music (Part Four: “Emperor” – chapters 11-23; 1935-1952; SHE, GONE WITH THE WIND [and losing the Oscar to THE WIZARD OF OZ], NOW VOYAGER, CASABLANCA, disappointment at a concert performance, opening for Sinatra, and rude critics, SINCE YOU WENT AWAY, his third Oscar, THE BIG SLEEP, Divorce and remarriage, THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE, KEY LARGO, JOHNNY BELINDA, THE FOUNTAIN HEAD, WHITE HEAT, etc.)

- Twilight years, end of the studio system, work scarce, family difficulties (Part Five: “Twilight of the Gods” – chapters 24-26; THE CAINE MUTINY, THE SEARCHERS, completing Victor Young’s CHINA GATE, A SUMMER PLACE, Max’s son’s suicide, Disney’s THOSE CALLOWAYS, Max’s final score, The Max Steiner Music Society is launched, Max’s death, remembrance, posthumous honors.)

Through the chapters on film music, Smith includes a very thorough listing of the “film scores to which Steiner contributed significantly as a composer during the years covered in each chapter.” In addition to all of this, Smith explores Max’s private life in detail, how it configured with, contrasted against, and affected his working life, and he covers nearly all of Steiner’s film scores. This is a fascinating and intricately detailed biography which adds plenty of new insight and closely examines the masterful movie music of Max Steiner. As with Smith’s earlier Bernard Herrmann bio, this is a must-have for any proper library of film music/cinema history books.

Smith closes his book with:

“To the general public, he is a forgotten figure. To cineastes, he is a historical footnote.

“But to any viewer watching a movie scored by Max Steiner, he remains a living presence. Everyday, somewhere on the planet, his work transports audiences into worlds larger than life in their heightened emotion, yet instantly relatable in their expressions of joy, pain, and romantic fulfillment.

“Just listen.”

Exactly.

AFTER THE SILENTS:

Hollywood Film Music in the

Early Sound Era, 1926-1934

By Michael Slowik

Columbia University Press, 2014

384 pages, paperback. $32.00

This is a comprehensive and well-researched analysis on a little-known portion of film music history. While Slowik’s primarily focus seems to be arguing that Max Steiner’s score for KING KONG (1933) was not, in fact, the first important attempt at integrating background music into sound film, the author also takes a close look at the industry’s early sound era (1926–1934), revealing a more extended and fascinating story. Rather than being the trailblazing musical achievement that many have so attributed, Slowik contends that KONG’s score actually drew upon many techniques which had been in place in film scores during the early sound films in years previous.

The book’s first five chapters produce a valuable exploration of the variety of film music strategies that were tested, abandoned, and kept in these early years following the rise of sound film. He explores early film music experiments and accompaniment practices in opera, melodrama, musicals, radio, and silent films and discusses the impact the advent of synchronized dialogue had on developing cinema. Chapter 5 (“Music and Other Worlds”) is of particular interest and it focuses on film music’s value to fantasy cinema.

Still, one can’t help feel that the studious examination of these prior scores serves only as a lead up to knock KONG’s place in film music history from its perch; but Slowik has some valid points which are worth considering. Many have taken for granted KONG’s status-quo as a stunningly innovative work from which the Golden Age of film music thereafter clearly sprung, but Slowik argues, based on his studious assessment of the music in more than two hundred films and their scores from the early sound era, that KONG’s music does not deserve its place of unique significance in the timeline of film musical achievement.

This thesis trickles through the book until the author lays out his position in the book’s sixth and final chapter, “Reassessing King Kong, or The Hollywood Film Score, 1933-1934.” Slowik’s research is scholarly and academic, and he brings to his discussion a credible and studious analysis of prior scores from the early period, in which his point-by-point examination indeed challenges the popular notion; while he recognizes the score’s effectiveness in its film, he argues that its influence as a groundbreaker in film music history is, in fact, unwarranted. This viewpoint will likely be a contentious one, daring to darken KONG’s more than eight-decades of musical supremacy as a groundbreaking work of fantasy cinema; but Slowik’s aim (I believe) is not to besmirch Steiner’s score as a magnificent work of film music in its own right; only to suggest that film music in its infancy was not wholly primordial and that the KONG score arose from years of previous film music development; it’s place atop Skull Mountain may be earned but it did not arise there by itself all of a sudden.

“At the very least, pre-KING KONG scores demonstrate that the use of nondiegetic music to convey the unfamiliar, exotic, or fantastic world was not a concept that sprang full-blown from the heads of KING KONG’s filmmakers,” Slowik writes in Chapter 6 as he begins his reassessment of the KONG score (p. 235). “Rather, it was a logical application of a preexisting film music assumption.”

As a lifelong admirer of the power of KONG’s score, I find Slowik’s arguments disturbing but compelling, and his intricate research tends to support his argument without actually besmirching the monumental effectiveness of Steiner’s music for the film. There’s value on Slowik’s meticulous appraisal of what place the KONG score belongs in the developing rise of Hollywood film music, although I do not find that his considered opinion has necessarily tarnished KONG’s regal reputation as a film score. In terms of general drama, adventure and suspense cinema, KONG may have drawn from prior advances, but its significance as a major work in the fantasy/monster movie genre remains untouched. None of the prior films Slowik references as predecessors of KONG’s musical stylings are within the same genre. However, there’s value in recognizing the antecedents this mighty score has in its film musical genealogy and giving these mostly-forgotten prior scores their proper due, while reserving for KING KONG its place as a masterful work in which the elements that were advanced in prior sound cinema came together in such a wonderful way to create a masterwork of fantasy filmmaking. KONG may not have arisen out of a void, but its use of what came before in the burgeoning growth of newfound genre had not been amalgamated in such a fine way as it was in the unforgettable saga of Kong and his beloved Ann.

The Struggle Behind the Soundtrack

The Struggle Behind the Soundtrack

by Stephen Eicke

McFarland & Co. Publishers, July 2019

220 pages, paperback. $45.

Order from Amazon

Stephen Eicke, otherwise known as the man behind Caldera Records, and prior to that was the editor-in-chief of Europe’s Cinema Musica magazine, has been exploring the making of film music for many years. The struggle that Eicke is concerned with and examines in this book is that of skilled film composers being hampered in their art, being held back by the very nature of commercial cinema, the stigma of work-for-hire, and the myriad changes of motion picture scoring in the digital age where old school styles have been overcome by the influence of mechanistic, remote control composition techniques. In his introduction, Eicke quotes composer David Raksin who late in his career bitterly complained that “It should be news to no one that many people believe the industry has been plundered, ruined by incompetence, and left to twist slowly in the wind by men whose principal interest… [does] not lie in filmmaking.” He also quotes Elmer Bernstein who in the late ‘90s stated, “I think it’s unfortunate that composers have a very difficult time getting a chance to write real film music, good film music.” These are not just grievances of semi-retired composers, wishing things were as they were in times past. Eicke also quotes Oscar-winning composer Mychael Danna, who remarks “There are a lot of forces that have made it more difficult to make scores that are serving the picture as well as they could, and second of all move the art forward,” while Emmy-winner Marco Beltrami seems similarly distressed when he states “I feel bad for the young composers who are up-and-coming. They have to deal with these problems.”

Intrigued by such concerns over current conditions in their profession, Eicke sought to investigate the merit of these claims and determine how changing conditions in technology, musical styles, commercial interests, the insistence on intensive mock-ups of film scores early in the process, the rising trend of digital samples replacing the purity of live orchestra performances, and production techniques dampening the skill and artistry of film composing in favor of imitating trends, embracing redundancy, and demanding more with less, is really having a negative effect on the art and science of film music. This book is a mostly objective assessment of the state-of-the-art of film music, incorporating interviews with more than 40 composers, editors, sound designers, and directors who provide their views about conditions under which film music exists in the current film industry.

Eicke’s perspectives are informed and well-intended, although perhaps overly pessimistic. I’ve found in my own interviews with hundreds of film composers over the last 45 years that composers tend to find very creative solutions to the problems they are often beset with in the industry, which is not to say the problems do not exist, but that good composers writing good film music tends to overcome them, but then I’ve maintained a pretty positive outlook over those 45 years, possibly to my own ignorance concerning actual working conditions, or perhaps not. Bottom line, Eicke’s book is a very interesting one by investigating a topic not elsewhere covered in film music books and daring to point a spotlight at struggles that lie within the film music workplace. There’s enough information at hand here to warrant consideration, and to lend some understanding of conditions under which composers have to work.

In the end, Eicke seems as disillusioned as Danna, Beltrami, and the others he’s spoken to. He recognizes how, in our digital age, virtually anyone with a computer and an understanding of creating musical sounds on it can eke out a film score that may not be inherently musical but may suffice lending a workable mood, and indicts the role of the temp score (as many do) as hampering creativity in favor of mimicking preexisting music [see composer Penka Kouneva’s guest article in my June 2019 column for an alternative viewpoint], and he offers a whole chapter in evaluating in detail how Remote Control Productions has changed the landscape of modern film music. Eicke writes in his concluding Summary that, like Elmer Bernstein recognized, “As society changes, so does the film industry, and with it, naturally, film music and the working conditions for its composers. It has always been a process of progress and setbacks.” Eicke closes with, “Political and societal changes will influence how we consume art and what kind of art we will consume. Will the result be more freedom for composers? Or even less? Everything is evolving. And so it goes.”

![]() Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words

Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words

By Ennio Morricone in Conversation with Alessandro De Rosa

Translated from the Italian by Maurizio Corbella

Oxford University Press, 2019.

341 pages, hardcover. $23.88

Order from amazon

Translated from the original 2016 Italian edition (Mondadori Libri S.p.A.), this is a thoroughly comprehensive examination of Ennio Morricone’s life and music as told by the composer himself in a series of in-depth conversations with composer De Rosa. He asks challenging and insightful questions, which Morricone answers in great detail. Maurizio’s Corbella’s English translation is superlative, making the volume a compelling read (far from the awkwardness of some of Morricone’s translated interviews) and an essential and intricate portrait of the composer and the man. Morricone speaks of his music, his technique, his relationships with various directors, his thoroughgoing understanding of music history, and his consummate views on creating music and composing for films versus “absolute music.” The book is exhaustively indexed, aiding its value as a research tool, but more over it’s a perceptive and enjoyable voyage through the mind of a true musical genius. He comments in various levels of detail on many of his scores. There is a 12-page insert of black and white and color photographs.

Some interesting samples from the text:

On Film Music as Background: “All too often, no less today than in the past, music is not considered as a language that concurs to shape the content of a film, but as something that plays in the background. Starting from this bias, film composers have themselves underestimated their own contribution, and in so doing they have made directors and producers accustomed to very fast working times, not the least by resorting to myriads of clichés.” (p. 79)

On Music and the Visual Image: I have always sought for new ways to interweave music and the other elements of a film, principally the visual ones, and respond to the demands I‘ve perceived in them… The only certainty I have is that music must be finely written, even when it is intended for a different art, another expressive form. It must be based on internal, formal and structural parameters, solid enough to hold its own independently from the images. At the same time, musical ideas must be attuned to the elements and suggestions of the specific cinematic context.” (p.96)

On Hiring Orchestrators: “I noticed a rather common trend in American cinema that I don’t approve. It would seem that entrusted this orchestration of a soundtrack to third parties is a totally usual praxis there. As it happens, famous composers sign scores when they have actually just written the themes… It was an immense delusion for me to find out about such widespread phenomenon, because I come from a background in which orchestration is an integral part of musical thinking, as much as melody, harmony, and every other musical parameter.” (p. 112)

On STAR WARS: “My criticism [is] not directed to the genre or to STAR WARS in particular, which I enjoyed a lot from the very beginning of the saga, but to the scoring style with which *(especially Hollywood) composers and directors have made us used to. What seems hazardous to me is to associate a march, no matter how well written, to outer space… I attempted a new direction with my score for THE HUMANOID… in which I devised a six-voice double fugue based on tonal harmony… Although that production could not remotely compete with STAR WARS, to me this piece seemed to somewhat mirror the imagin[ation] of the universe, the infinite spaces and the sky, without giving in to clichés.” (p. 113).

On Rejected Scores: “It is immensely painful when a director refuses my music at the recording stage… You get your recording done and someone tells you they don’t like any of it… In my first experiences I was anguished, I still am in a way, by the desire to do my job well, to serve the film and satisfy the director’s expectations and personal taste… but without giving up mine and those of the public. (p. 130, 131).

On Communications: “Also troubling is when directors are too shy to tell you that they are not convinced. To that I must add my own shyness, which inhibits me from asking ‘Do you like it or not?’… Sometimes directors don’t have a clear idea after the first round of listening and need more time. Their role entitles them to imagine a certain kind of music for their film; for this reason they may expect the composer to go in the same direction they have in mind… When directors speak out about their skepticism in time, they give me a chance to understand what new directions to take, though at times I’ve refused to do so.” (p. 131).

On The Future of Music: “The attention to sound is fundamental for me; the counterpoint of timbres is crucial. I don’t conceive of music’s future devoid of intervals – a music merely made of ambient sounds and electronics… We must never forget that we not only have rhythm, harmony, and melody at our disposal, but countless other parameters that have been neglected for centuries, even if rightly so… How can I answer your question if not by saving that we shouldn’t prevent ourselves from being as open and curious to all of the sound resources and possibilities available to us?” (p. 255).

![]() Life Notes

Life Notes

By Ennio Morricone

(Translator not credited)

Musica e Oltre srl., 2019

Hardcover, 128 pages. £30.00

Order from firebrand.com (UK).

This book makes a nice and more informal companion to In His Own Words (above). Take a walk with Ennio Morricone through this a first person account of key childhood memories, anecdotes from his career and reflections on music and family life. Through seven short-ish chapters, the maestro takes the reader through his childhood (“I believe I was born to be a musician.”), how he learned to compose music (“I was fixated on studying under [Goffredo] Petrassi. I refused to attend at all unless I was put under his tutelage and from September to Christmas I did not go to composition classes. Finally they relented and added me into Petrassi’s class.”), his early career in writing music and arranging songs for the record industry (“I never told Petrassi about this as I was sure he would judge it a waste of time and a corruption of my learning process. However, when he did find out he was not cross at all but simply reassured me he was confident I could make up for the time I was wasting on it at a later stage.”), the Cinema Years (“I need trust to work well with a film director. It is essential if I am to work with a director more than once. I am fortunate in having had a number of trusting and, therefore, successful professional partnerships in this area of my work.”), his ongoing passion for absolute music (“Absolute music, or pure concert music, is my great passion. Composing absolute music is private and a personal endeavor just as it is a personal experience for the one listening.”), the family life he shared with his wife and four children (“The joys and frustrations of a large family are wonderful but I reject totally the idea that composers put their very private suffering or happiness into their music. Music is a talent not an expression of personal feelings.”), and a final glimpse into the present and future (“I like to keep moving forward in life. In my Oscar ceremony acceptance speech I said that receiving the honor from the Academy was a point to progress from, a starting point and not a destination. I do not like to look back. A constant search for self-awareness avoids passivity.”) A pair of appendices provide summary discographies of both film music recordings and absolute music releases (citing only first releases). The volume is full of photos, black & white and color. While not as thoroughly comprehensive as the De Rosa book, it’s nonetheless a compelling, informal, and compact autobiography of the composer’s life and experiences, and is a welcome addition to any proper library of film music studies or composer bios.

Music in Science Fiction Television:

Music in Science Fiction Television:

Tuned to the Future

Routledge Music and Screen Media Series

Edited by K. J. Donnelly and Philip Hayward

New York & London: Routledge, 2013.

Paperback, 228 pages.

https://www.routledge.com/

This omnibus collection of academic-styled essays provided a wealth of details on televised science fiction from THE TWILIGHT ZONE, THE JETSONS, and LOST IN SPACE through TV’s STAR TREK franchise, Germany’s RAUMPATROUILLE, UK’s SPACE: 1999 and DOCTOR WHO (both classic and revived), through the more recent BABYLON 5, LOST, and even a thorough examination of low-budget sound in SyFy’s 4-season hit SANCTUARY. Both editors are very capable and have compiled an excellent group of authors both qualified and articulate in investigating the topic at hand – Donnelly has edited or co-edited the essay collections Partners in Suspense: Critical Essays on Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock (2017), and others, while Hayward is known for editing such notable volumes Terror Tracks: Music, Sound and Horror Cinema (2009) and Off The Planet: Music, Sound and Science Fiction Cinema(2004), etc. Their contributors are almost all scholars, professors, or instructors in academia whose experience allows them to address the topic in a considerate and professional manner.

Focusing specifically on television science fiction series with a properly international (or at least American/European) perspective allows for a comprehensive consideration of what is unique about television s.f. and the differences in budget, deadlines, and sonic palette in crafting musical accompaniment on the small screen for serialized storylines of 30- to 60-minutes in length (usually), which are all largely very different challenges from those of feature films (“Television is not the same as film despite similarities and crossovers between the two,” the author’s write in their preface. “It has regularly been produced more frugally…”). The book’s only potential drawback is that is narrows its attention to a small number of very specific television shows, so can’t be considered an overall viewpoint of TV science fiction music as a whole – but it isn’t trying to be. By selecting a baker’s dozen of representative shows, the book is able to delve into those particular samples to detail how they serve as individual exemplars of the medium.

As the editors also note in their Preface, “The programs analyzed [herein] belong to the broad genre of science fiction, which can be summarized as an aggregation of works substantially concerned with aspects of futurism, imagined technologies, aliens, and/or interplaneterism. As a genre primarily defined in terms of iconography, locale, and thematics, the television programs analyzed in this volume also incorporate elements of the thriller, action, and comedy genres. In addition their soundtracks also draw on related conventions.” The range of matters evaluated in the essays run from the early mix of electronic sound effects and music found in the DOCTOR WHO episodes of the early 1960s to the more technologically sophisticated hybrid sound design of our modern day, as the authors also point out: “Science fiction dramas are often about human possibilities and potentials, and consequently their sound and music can be about humanity’s sonic present and future, and sonic capabilities.”

The essays are rich in thorough exploration; some are accompanied by photographs from the shows discussed, some include musical examples which will be very useful for those who read music. The essays are valuable in their depth of exploratory assessment, each chapter best savored for consideration via its own analytical discourse rather than absorbing the book as a whole, although by the time one is finished, one with have gained a useful understanding of much of what lies behind with within the depths of scoring science fiction television. “Some of the most outrageous and avant garde music widely distributed since the middle of the twentieth century has used the medium of science fiction television,” Donnelly and Hayward conclude in their preface. “Equally, so has some music of high quality and some music of great popularity. All of which makes television’s science fiction genre particularly interesting with respect to its sonic aspects.”

Experiencing Film Music: A Listener’s Companion

By Kenneth LaFave

Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017

Hardcover, 214 pages, $40

www.rowman.com

There have been a number of books focusing on the history of film music published in the last ten to twenty years, each overview providing its own perspective and summation of where film music began and how it has affected cinema since the dawn of the silent era. Some have focused on composers, some on how musical scores have changed across the decades, others have been organized around how various cinematic genres have been treated musically. Kenneth LaFave favors the latter format, and as the most recent book to cover the whole of cinema music it is of special interest as it analyzes film scoring up to the very near present, at least a decade further than most other historical examinations have gone by virtue of being published a decade or more in the past.

La Fave covers American films specifically, leaving a detailed analytical history of European, Asian, and worldwide film music trends, composers, and history still somewhere in the future. But La Fave is quite thorough in his compact inspection of Hollywood/US based film music, and his narrative is wonderfully readable, devoid of academic stylisms and copious score reproductions that can hamper understanding of more scholarly-focused works by those not possessing the ability to read music or understand musical terminology at an academic level. As La Fave writes in his introduction, “This book is not offered as a scholarly last word on the art of writing music for the cinema… It is, rather, a set of observations on the history of that art and some of its major practitioners, a look at how they worked and why the music they wrote sounded the way it did, along with some hints about how to appreciate their music in the context of film.” By examining film music as an experience, rather than as a scholarly study, the author stays true to the status of film music as an emotional encounter, one to be felt as much as studied as a science or a craft.

In its relatively short space of 200+ pages, La Fave provides plenty of detailed observation which will likely prompt further study and exploration (“the text reflects my own tastes and particular interests,” he writes, concluding his introduction. “Beyond that, readers are advised to explore film music on their own, using this book as a guide.”). Beginning with the not-so-Silent-Era, La Fave inspects the origins and developments that brought movie music into its own as a form of collaborative art. Chapter 2 surveys film music’s first generation, paying particular scrutiny to Max Steiner and his KING KONG score as the archetype of thematic film scoring of the early decade. Chapter 3 moves into mysteries, thriller, and film noir with a look at films like SUNSET BOULEVARD, TOUCH OF EVIL, and CHINATOWN before settling in to examine Bernard Herrmann in some detail, particularly VERTIGO and PSYCHO. Next we have a look at music in epic, exotics, and war, including THE LION IN WINTER (the author’s avowed favorite John Barry score), Jarre’s LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and, nicely, RYAN’S DAUGHTER, and Nino Rota’s GODFATHER scores. A chapter on “Cowboys and Superheroes” discusses the wide range of these two genres, with the former going over the work of Tiomkin, Moross, Bernstein, Alfred Newman and Morricone, and the latter quite briefly assessing Elfman, Christophe Beck, and Hans Zimmer’s roles in developing music for the heroic musclebound. Science fiction, drama, comedies, romantic comedies, and the use of theme songs and jazz in film scores, and more bring the book to a close, all with a very informed, engaging narrative. It’s a book that beckons to be read and furnishes a pleasing analytical overview of its varied topics. Highly recommended for its readability, broad scope of coverage, and its relative brevity, which indeed, as intended, stimulates the reader to embrace what the book has to offer and launch into further study on one’s own with additional resources.

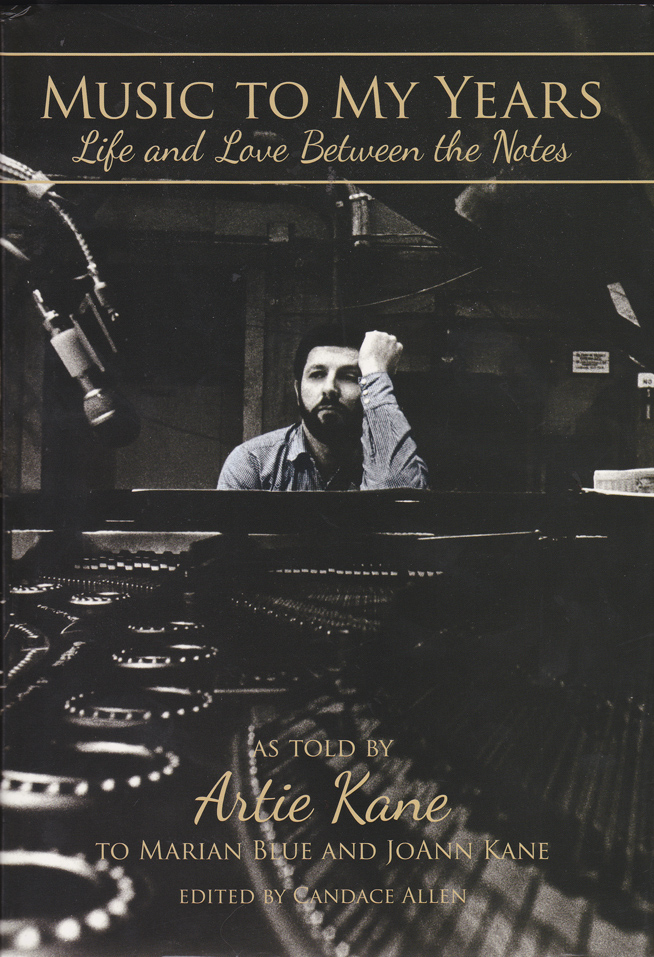

MUSIC TO MY YEARS

MUSIC TO MY YEARS

Live and Love Between the Notes

By Artie Kane as told to Marian Blue & JoAnn Kane

Venice, CA: Amphora Editions, 2017.

355 pages, hardcover.

www.AmphoraEditions.com

Composer Artie Kane has been a musical mainstay on radio, stage, and screen for more than half a century. In this thick and engaging autobiography, Artie gathers together his experiences as a pianist for Hollywood studios (1960-78), film composer (more than 250 television shows and 7 feature films, 1976-1994), and conductor (60-some motion picture scores, 1991-1999) and tells his story in a comfortably readable style. This is a thick, impressively heavy book brimming with full color images printed on substantial, acid-free pages in the welcoming Garamond font; it’s also thick with details that cover the author’s life in modest and memorable description. The back stories behind Artie’s life and work are a pleasure to read as he revisits them for us, filling us in on the details of how this child prodigy from Columbus, Ohio achieved a lifelong career in Hollywood and worked on some of its most memorable productions, from television’s WONDER WOMAN, THE LOVE BOAT, HOTEL, DYNASTY, and MATLOCK, to feature films like Irving Kershner’s THE EYES OF LAURA MARS, Robert Butler’s NIGHT OF THE JUGGLER, and Richard Brooks’ WRONG IS RIGHT – not to mention an ongoing succession of made-for-TV movies of various beloved genres. Artie’s love for his “mother, eight wives, four girlfriends, and three sons,” as he cites them in his dedication, are strong, but all are subservient to his piano, his singular constant, which “lives at the center of my world.” Music to My Years is essentially the story of his love affair with the piano – and all manner of music which has been propelled by his mastery of the instrument over the years – and also with those others mentioned that have filled his life and sought-for love over his fifty years in entertainment music. He respects and loves them all, making these memoirs fond and enthusiastic, and a delight to read. I quite enjoyed stepping into Artie Kane’s shoes, through this book, and taking the long stroll through his life. Artie: you have shared so much of yourself, musically, with us over the decades – thank you now for sharing your actual self!

Let’s Get Monster Smashed:

Let’s Get Monster Smashed:

Horror Movie Drinks for a Killer Time

Jon Chaiet & Marx Chaiet

144 pages, Schiffer Publishing, 2017

This is a fascinating book that isn’t really about films or film music directly. But fans of films and film music may well find it useful as it’s about preparing drinks to enjoy while having a good time watching your favorite or even hitherto unwatched horror movie. It’s kind of like one of those Tiki bar cocktail recipe books that you find among the exotica crowd, perhaps with a FROM HELL IT CAME twist or even a “Cocktails to drink while fleeing from your Zuni Fetish Doll while Bob Cobert’s score augments the creepiness” connotation.

This delightful hardback book is the shape and size, more or less, of a “Big Box” VHS tape, albeit not as thick. But it contains 55 potables peculiar to watching vintage ‘80s gore-infused VHS horrors, video nasties, and guilty pleasures from Troma, Full Moon, and the like. It’s a “twisted tome devoted to vitality, villains, and VHS,” as the back cover promo verbiage intones. “Like all of your favorite horror movies, the recipes herein are a mix of vintage tropes and new classics; weirdly wonderful and unexpectedly unique… “Muster your minions and savor as you spectate – these potables are party-sized and paired with classic & kitschy horror pictures for maximum merriment.”

We’re talking crude concoctions like “Tad’s Tangy Tumbler,” a foamy mixture of pomegranate juice, salt, and soy lecithin just perfect for watching the sloppy slobber of CUJO munching on the neighbors, or this razor-sharp brew of “Blade” – lemon juice, syrup, and gelatin recommended for drinking while watching PUPPET MASTER 2, or “The Skin Suit” with its taut and twisted tumblerful of tequila, lime juice, and jalapeno syrup, just feel its grimy gusto slipping down your throat while enjoying SILENCE OF THE LAMBS.

And on and on – 144 pages of salacious spirits inspired by video horrors from the classic to the nasty, illustrated by grim and ghastly multicolored drawings and shaken & stirred into five essential chapters for your eager ingestion, “Monster Shots,” “Gelatinous Gulps,” “Potions& Grog,” “Smoke & Mirrors,” and “Virgin Sacrifices.”

This is a fun book even for non-drinkers, as its contents can be a fearful infusion of entertainment all on its own – simply as a perilous perusal of its disturbing draughtsmanship may additionally serve as a distraction while avoiding the unwatchable entertainment of ROBOT MONSTER or perhaps making even the most superbly guilty pleasure of ’70s or ’80s video grotesquerie a bit easier to swallow.

Highly recommended to tickle your tastebuds and please your palate, and putting a little extra punch into your movie viewing pleasure.

It Came from the Video Aisle!

It Came from the Video Aisle!

Inside Charles Band’s Full Moon Entertainment Studio

Dave Jay, William S. Wilson, and Torsten Dewi

480 pages, Schiffer Publishing 2017

This is a thick and very comprehensive look behind Full Moon Entertainment, best known for unleashing a slew of low budget, popular, often iconic, quite entertaining and nasty little horror movies from 1888 through the present day. Divided into lengthy chapters that cover each of the studio’s various eras of production, which fairly neatly coincide with the company’s various stages of production, from Band’s creation of Full Moon Productions following the collapse of his previous film studio, Empire Pictures, and the release of Full Moon’s emblematic hit PUPPET MASTER in 1989 through various subordinate studio titles up to its most recent and current embodiment of Full Moon Pictures. Each of the studio’s primary franchises are discussed in detail (in addition to the PUPPET MASTER series, there are the GINGERDEAD MAN, KILLJOY, SUBSPECIES, and EVIL BONG movies), as well as one-shot productions (like DOCTOR MORDRID, MANDROID, and many others) and its distribution of films from other, similarly minded filmmakers. The three writers provide various components of each chapter as well as interviews with Full Moon filmmakers, and it’s a very comprehensive studio of the vast filmmaking empire that followed Band’s Empire. The only drawback that comes to immediate attention is the book’s lack of an index, which will frustrate researchers looking for tidbits of information that could be anywhere in a book as thick as this one. For example, seeking what the book may have to share about composer Richard Band, Charles’ brother and the musical mainstay of a large number of Charles’ movies, you’ll be stymied at having to peruse literally the whole book, page-by-page or at least section-be-section to discover anything about his work for Full Moon – which, unfortunately, seems to be very little based on a cursory rummaging through its pages. Perhaps a minor point, indeed, compared to the main thrust of the book which is to document the rise and accomplishments of Full Moon filmmaking empire that Charles Band built, and in that respect the book does fulfill its intent in a thoroughly detailed manner.

Universal Terrors 1951-1955: Eight Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Films

By Tom Weaver with David Schecter, Robert J. Kiss, and Steve Kronenberg.

McFarland, 2017

440 pages, $49.99.

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Tom Weaver’s second (of three intended) books analyzing 1930-1960 sci-fi cinema in comprehensive detail is a follow up on Universal Horrors, The Studio’s Classic Films 1931-1946, published in a second edition in 2007, covering FRANKENSTEIN and DRACULA 1931 through SHE-WOLF IN LONDON and THE BRUTE MAN in 1946. Along with the current volume, and a third volume to come (covering 1956 presumably through 1959), these books, as well as 2014’s close cousin, The Creature [from the Black Lagoon] Chronicles (2014), serve as a marvelously detailed overview of these films. Universal Horrors, giving some license for what was actually horror and what was perhaps close but not quite, covered some 75 movies; by cutting back its coverage into only eight movies, Universal Terrors, allows for tremendous detail and covering far more aspects of the films than was accomplished in the first volume. Taking an idea from The Creature Chronicles, where Weaver was assisted by Steve Kronenberg and classic horror and sci-fi music expert David Schecter to include wide-ranging coverage of the film’s music, Schecter was invited back among the quartet of writers covering Universal Horrors; he contributes a significant sheaf of pages to cover the music of these eight classic films. Thus the book’s audience is expanded from 1950s horror and science fiction movie fans, but film music fans as well, and is sure to become a first-rate, widely detailed reference source for genre film music of this decade. In a time when serious discussion and examination of these films began (with Carlos Claren’s groundbreaking 1967 volume A History of the Horror Film) first exposing the horror genre to serious discussion and evaluation, music has all too often been left out of that discussion except in the most obvious of circumstances. By placing an equal focus on the musical quotient of these respected films – some of them even revered, Weaver and his compatriots, each an expert in a certain aspect of their cinematic-literary study, have provided an enriched encyclopedic analysis of these films from each’s unique perspective. The thorough explanation from Schecter of the usage of music to enhance these films’ interactive potency is very welcome.

Tom Weaver’s second (of three intended) books analyzing 1930-1960 sci-fi cinema in comprehensive detail is a follow up on Universal Horrors, The Studio’s Classic Films 1931-1946, published in a second edition in 2007, covering FRANKENSTEIN and DRACULA 1931 through SHE-WOLF IN LONDON and THE BRUTE MAN in 1946. Along with the current volume, and a third volume to come (covering 1956 presumably through 1959), these books, as well as 2014’s close cousin, The Creature [from the Black Lagoon] Chronicles (2014), serve as a marvelously detailed overview of these films. Universal Horrors, giving some license for what was actually horror and what was perhaps close but not quite, covered some 75 movies; by cutting back its coverage into only eight movies, Universal Terrors, allows for tremendous detail and covering far more aspects of the films than was accomplished in the first volume. Taking an idea from The Creature Chronicles, where Weaver was assisted by Steve Kronenberg and classic horror and sci-fi music expert David Schecter to include wide-ranging coverage of the film’s music, Schecter was invited back among the quartet of writers covering Universal Horrors; he contributes a significant sheaf of pages to cover the music of these eight classic films. Thus the book’s audience is expanded from 1950s horror and science fiction movie fans, but film music fans as well, and is sure to become a first-rate, widely detailed reference source for genre film music of this decade. In a time when serious discussion and examination of these films began (with Carlos Claren’s groundbreaking 1967 volume A History of the Horror Film) first exposing the horror genre to serious discussion and evaluation, music has all too often been left out of that discussion except in the most obvious of circumstances. By placing an equal focus on the musical quotient of these respected films – some of them even revered, Weaver and his compatriots, each an expert in a certain aspect of their cinematic-literary study, have provided an enriched encyclopedic analysis of these films from each’s unique perspective. The thorough explanation from Schecter of the usage of music to enhance these films’ interactive potency is very welcome.

A Dimension of Sound: Music in THE TWILIGHT ZONE

Reba A. Wissner

318 pages, paperback. Pendragon Press, 2013

http://www.pendragonpress.com/book.php?id=725

In 2013 Pendragon Press launched a series entitled “Music in Media” with this book as its inaugural release. The book is a thorough examination of this seminal TV anthology show’s use of music – through which many composers, including Jerry Goldsmith, Fred Steiner, Nathan Van Cleave, and others began their film musical careers, and others, including Bernard Herrmann, Franz Waxman, Leith Stevens, Leonard Rosenman, William Lava and others found a place for continued challenging work after the end of the studio system that occupied most of their careers. Featuring an introduction by Tommy Morgan, whose distinctive harmonica playing made it into several TZ scores, including “The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank,” performed entirely on solo harmonica, Wissner offers individual chapters to the show’s four primary composers (Goldsmith, Steiner, Herrmann, Van Cleave), while covering less frequent composers in a chapter of their own. Very well researched, the author covers the subject in terms of its dramatic effect on the storytelling as well as from a musical perspective, with numerous score samples. An earlier chapter covering the techniques of composing and recording for the show includes some examples of timing notes and other charts the composers had to work with. An appendix offers a very valuable index of those episodes whose original cues were later reused throughout the series. This is a fine book for those interested in how this influential series utilized music while also offering an understanding of the ways in which music – both original and stock – can be used in an anthology series. The subject matter is both timely and extremely pertinent; the influence of what TWILIGHT ZONE and its composers did with music continues to be felt in the more musical-savvy of today’s television programming, and the use of music across the show’s five season remains a textbook example of how music can be used to enhance and interact with what is happening on the screen and felt through its storytelling. – rdl

In 2013 Pendragon Press launched a series entitled “Music in Media” with this book as its inaugural release. The book is a thorough examination of this seminal TV anthology show’s use of music – through which many composers, including Jerry Goldsmith, Fred Steiner, Nathan Van Cleave, and others began their film musical careers, and others, including Bernard Herrmann, Franz Waxman, Leith Stevens, Leonard Rosenman, William Lava and others found a place for continued challenging work after the end of the studio system that occupied most of their careers. Featuring an introduction by Tommy Morgan, whose distinctive harmonica playing made it into several TZ scores, including “The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank,” performed entirely on solo harmonica, Wissner offers individual chapters to the show’s four primary composers (Goldsmith, Steiner, Herrmann, Van Cleave), while covering less frequent composers in a chapter of their own. Very well researched, the author covers the subject in terms of its dramatic effect on the storytelling as well as from a musical perspective, with numerous score samples. An earlier chapter covering the techniques of composing and recording for the show includes some examples of timing notes and other charts the composers had to work with. An appendix offers a very valuable index of those episodes whose original cues were later reused throughout the series. This is a fine book for those interested in how this influential series utilized music while also offering an understanding of the ways in which music – both original and stock – can be used in an anthology series. The subject matter is both timely and extremely pertinent; the influence of what TWILIGHT ZONE and its composers did with music continues to be felt in the more musical-savvy of today’s television programming, and the use of music across the show’s five season remains a textbook example of how music can be used to enhance and interact with what is happening on the screen and felt through its storytelling. – rdl

We Will Control All That You Hear

THE OUTER LIMITS and the Aural Imagination

Reba A. Wissner

242 pages, paperback. Pendragon Press, 2016

http://www.pendragonpress.com/book.php?id=748

Following the author’s 2013 volume, A Dimension of Sound: Music in the Twilight Zone, this third volume in Pendragon’s “Music in Media” series focuses on the second major television anthology of the early ‘60s and its creative use of music. Reba A. Wissner has provided a comprehensive analysis of the series’ use of music, both newly composed scores and stock music, to interact with the stories being played out on screen, enhancing their sense of drama, wonder, and disturbiana. The first three chapters set up background basics, explain the common practice of recycling cues out of a studio’s library of music, and how orchestration and sound design provides the final ingredients for an interactive score. The final two chapters examine in detail the scores of Dominic Frontiere for season 1 (and also Robert Van Eps, Frontiere’s former teacher who was brought in to compose music for several episodes), and that of Harry Lubin for season 2. Rather than examining the music episode by episode (which would have been impractical, especially due to the re-use of cues over many episodes), Wissner opts for a more coherent examination oriented around a topical design (“Gearing the Unseen,” “Ethnic Identities,” “Music and Gender,” “Creatures Big, Small, and Gooey,” and the like). Very well researched and organized, Wissner’s analysis of the series’ limitless outré musical design is an authoritative and definitive one. Her research has discovered much which had not been previously known or revealed (such as Van Eps having composed more than just the “Tourist Attraction” episode and the jazz source cues from “The Day After Doomsday” that he’d been credited with previously). Music samples are provided for those who read music, but Wissner’s narrative style never becomes so scholarly and obscured by musicological terminology that it loses readability for those who don’t have an academic musical education. Alongside her previous TWILIGHT ZONE book, Wissner’s OUTER LIMITS music assessment is a significant entry to genre film music studies as well as being a welcome read for the film score fan. – rdl

Following the author’s 2013 volume, A Dimension of Sound: Music in the Twilight Zone, this third volume in Pendragon’s “Music in Media” series focuses on the second major television anthology of the early ‘60s and its creative use of music. Reba A. Wissner has provided a comprehensive analysis of the series’ use of music, both newly composed scores and stock music, to interact with the stories being played out on screen, enhancing their sense of drama, wonder, and disturbiana. The first three chapters set up background basics, explain the common practice of recycling cues out of a studio’s library of music, and how orchestration and sound design provides the final ingredients for an interactive score. The final two chapters examine in detail the scores of Dominic Frontiere for season 1 (and also Robert Van Eps, Frontiere’s former teacher who was brought in to compose music for several episodes), and that of Harry Lubin for season 2. Rather than examining the music episode by episode (which would have been impractical, especially due to the re-use of cues over many episodes), Wissner opts for a more coherent examination oriented around a topical design (“Gearing the Unseen,” “Ethnic Identities,” “Music and Gender,” “Creatures Big, Small, and Gooey,” and the like). Very well researched and organized, Wissner’s analysis of the series’ limitless outré musical design is an authoritative and definitive one. Her research has discovered much which had not been previously known or revealed (such as Van Eps having composed more than just the “Tourist Attraction” episode and the jazz source cues from “The Day After Doomsday” that he’d been credited with previously). Music samples are provided for those who read music, but Wissner’s narrative style never becomes so scholarly and obscured by musicological terminology that it loses readability for those who don’t have an academic musical education. Alongside her previous TWILIGHT ZONE book, Wissner’s OUTER LIMITS music assessment is a significant entry to genre film music studies as well as being a welcome read for the film score fan. – rdl

Scored to Death: Conversations with Some of Horror’s Greatest Composers

J. Blake Fichera

356 pages, paperback, Silman-James Press, 2016

Scored to Death delves specifically and deeply into the minds of noted horror film composers. Fichera, who is both a film editor and a musician himself, has assembled a first rate collection of interviews, presented in straightforward Q&A format, and he asks both challenging and educated questions about the art and science of scoring the suspenseful and the scary. The book isn’t a narrative overview of the genre’s music, but rather a gathering of interviews by the author of fourteen composers who have either focused on the genre or made significant contributions to its music. Included are Nathan Barr (CABIN FEVER, HOSTEL), Charles Bernstein (A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET), Joseph Bishara (THE CONJURING, INSIDIOUS), Simon Boswell (LORD OF ILLUSIONS), John Carpenter (HALLOWEEN), Jay Chattaway (MANIAC), Fabio Frizzi (ZOMBI 2, THE BEYOND), Jeff Grace (HOUSE OF THE DEVIL, THE INNKEEPERS), Maurizio Guiarini (SUSPIRIA, CONTAMINATION as a member of Goblin), Tom Hajdu (of tomandandy: RESIDENT EVIL: RETRIBUTION, SINISTER 2), Alan Howarth (HALLOWEEN 2-6), Harry Manfredini (FRIDAY THE 13TH series, HOUSE series), Claudio Simonetti (DEMONS, DRACULA 3D), and Christopher Young (HELLRAISER, DRAG ME TO HELL). Fichera’s interviews are hefty and comprehensive, and represent a good of major horror scorers from the 1980s to the present day. As a whole the book presents a thorough examination of the composers’ perspective toward scoring horror cinema.

Scored to Death delves specifically and deeply into the minds of noted horror film composers. Fichera, who is both a film editor and a musician himself, has assembled a first rate collection of interviews, presented in straightforward Q&A format, and he asks both challenging and educated questions about the art and science of scoring the suspenseful and the scary. The book isn’t a narrative overview of the genre’s music, but rather a gathering of interviews by the author of fourteen composers who have either focused on the genre or made significant contributions to its music. Included are Nathan Barr (CABIN FEVER, HOSTEL), Charles Bernstein (A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET), Joseph Bishara (THE CONJURING, INSIDIOUS), Simon Boswell (LORD OF ILLUSIONS), John Carpenter (HALLOWEEN), Jay Chattaway (MANIAC), Fabio Frizzi (ZOMBI 2, THE BEYOND), Jeff Grace (HOUSE OF THE DEVIL, THE INNKEEPERS), Maurizio Guiarini (SUSPIRIA, CONTAMINATION as a member of Goblin), Tom Hajdu (of tomandandy: RESIDENT EVIL: RETRIBUTION, SINISTER 2), Alan Howarth (HALLOWEEN 2-6), Harry Manfredini (FRIDAY THE 13TH series, HOUSE series), Claudio Simonetti (DEMONS, DRACULA 3D), and Christopher Young (HELLRAISER, DRAG ME TO HELL). Fichera’s interviews are hefty and comprehensive, and represent a good of major horror scorers from the 1980s to the present day. As a whole the book presents a thorough examination of the composers’ perspective toward scoring horror cinema.

Film and Television Scores, 1950-1979: A Critical Survey by Genre

Kristopher Spencer

366 pages, paperback, McFarland & Co., 2008

Kristopher Spencer’s book takes an unusual but highly effective approach in its examination of music for movies. Noting the significant change that transformed Hollywood film scores as the Golden Age waned and the advent of pop, jazz, rock, avant-garde, and other styles began to be assimilated into film scores, Spencer, the founder of scorebaby.com, illuminates the “Silver Age” of movie music in this winning and very readable volume. The composers of this era of film music history “changed the way movie music was made,” asserts Spencer, who examines in depth the changing role of music in seven genres of moviemaking: crime thrillers, spy movies, sexploitation films (think LOLITA, BARBARELLA, VAMPIROS LESBOS, LAST TANGO IN PARIS), Westerns, science fiction, horror films, and rock and roll movies. While the latter might be obvious in its use of music, Spencer explores the changing role of rock music as a song soundtrack to such films as THE ENDLESS SUMMER, THE WILD ANGELS, THE TRIP, EASY RIDER, THE GRADUATE, SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, and many others, and shows how the beat-and-rhythm heavy music had its own place aside more dramatic and progressive orchestral film scores. Each chapter includes a dozen recommended soundtracks for your buying or bidding pleasure, and the result is a fascinating look at the evolving world of film music as it pertained to specific genres of film music during its Silver Age. Spencer’s evaluation of horror film music, for example, is a concise overview of the use of music in films of Roger Corman, Hitchcock, Hammer, and others, including a prolonged and very fascinating overview of music in Italian giallo horror films of the 70s. Spencer’s long chapter on Western scores proffers up an excellent summation of the music for Italian and German Western films and the groundbreaking effect of Italian Western music on so much of cinema. The chapter on science fiction scores evaluates the progression from 60’s pop, atonal sci-fi music, and the resurgence of symphonic film music in the later 1970s. There’s not an extensive musical analysis of individual films or composers, but there is a perceptive overview of the kind of music that embellished these movies and how that kind developed and changed over the three decades covered by this book. In all of this Spencer calls out attention to significant nuances in the development and style of genre film scoring and illuminates much of the music for these types of films, and their musical relationship together as members of the same genre (or sub-genre, or sub-sub-genre, in some cases), that is valuable to any serious study of movie music.

Kristopher Spencer’s book takes an unusual but highly effective approach in its examination of music for movies. Noting the significant change that transformed Hollywood film scores as the Golden Age waned and the advent of pop, jazz, rock, avant-garde, and other styles began to be assimilated into film scores, Spencer, the founder of scorebaby.com, illuminates the “Silver Age” of movie music in this winning and very readable volume. The composers of this era of film music history “changed the way movie music was made,” asserts Spencer, who examines in depth the changing role of music in seven genres of moviemaking: crime thrillers, spy movies, sexploitation films (think LOLITA, BARBARELLA, VAMPIROS LESBOS, LAST TANGO IN PARIS), Westerns, science fiction, horror films, and rock and roll movies. While the latter might be obvious in its use of music, Spencer explores the changing role of rock music as a song soundtrack to such films as THE ENDLESS SUMMER, THE WILD ANGELS, THE TRIP, EASY RIDER, THE GRADUATE, SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, and many others, and shows how the beat-and-rhythm heavy music had its own place aside more dramatic and progressive orchestral film scores. Each chapter includes a dozen recommended soundtracks for your buying or bidding pleasure, and the result is a fascinating look at the evolving world of film music as it pertained to specific genres of film music during its Silver Age. Spencer’s evaluation of horror film music, for example, is a concise overview of the use of music in films of Roger Corman, Hitchcock, Hammer, and others, including a prolonged and very fascinating overview of music in Italian giallo horror films of the 70s. Spencer’s long chapter on Western scores proffers up an excellent summation of the music for Italian and German Western films and the groundbreaking effect of Italian Western music on so much of cinema. The chapter on science fiction scores evaluates the progression from 60’s pop, atonal sci-fi music, and the resurgence of symphonic film music in the later 1970s. There’s not an extensive musical analysis of individual films or composers, but there is a perceptive overview of the kind of music that embellished these movies and how that kind developed and changed over the three decades covered by this book. In all of this Spencer calls out attention to significant nuances in the development and style of genre film scoring and illuminates much of the music for these types of films, and their musical relationship together as members of the same genre (or sub-genre, or sub-sub-genre, in some cases), that is valuable to any serious study of movie music.

Hammer Film Scores and the Musical Avant-Garde

by David Huckvale

225 pages, paperback, McFarland & Co., 2008

With this third book devoted specifically to music for Hammer horror films (the first was my general overview Music from the House of Hammer, in 1986; the second was Huckvale’s own James Bernard, Composer to Count Dracula in 2006), Huckvale further explores what it was that made music for Hammer’s brand of horror cinema special and so uniquely flavorful. Huckvale takes a mostly musicological approach in his analysis, grouping Hammer’s composers by style as they embodied or contrasted with the modern musical avant-garde which, according to the author, was largely introduced to the popular culture through film music such as that of Hammer. While other studios were still holding fast to Gothic romanticism (as Hammer did to an extent, mostly with the works of James Bernard and Harry Robinson) or embracing pop music styles, Hammer more than any other studio of the day encouraged composers to articulate musical modernism into their scores. Thus we have the modernism of Elisabeth Lutyens (PARANOIAC), Malcolm Williamson (BRIDES OF DRACULA), and Humphrey Searle (THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS), Mario Nascimbene (ONE MILLION YEARS, B.C.) and Tristram Cary (QUATERMASS AND THE PIT), the modern gothic sensibilities of Mike Vickers (DRACULA A.D. 1972) and John Cacavas (THE SATANIC RITES OF DRACULA), the significant serialism of Benjamin Frankel (CURSE OF THE WEREWOLF), and the innovative modernist of Paul Glass (TO THE DEVIL… A DAUGHTER) discussed in detail and as linchpins of Huckvale’s treatise. Huckvale begins his examination of Hammer film music, after introducing the studio’s three main musical directors during their horror period – John Hollingsworth, Philip Martell, and Marcus Dodds – with a chapter about classical composer Arnold Schoenberg, whose influence on musical modernism and serialism has been greater than any other composer (Schoenberg’s 12-tone system virtually defined and standardized musical modernism). What follows is then an examination of Hammer’s film music on these terms. While in the minds of many, it was 19th Century gothic romanticism that was preeminent in Hammer’s musical style; but Huckvale perceptively points out that there was more to Hammer than the inspiration of the 19th Century: “Much of the music for which [Hammer’s musical directors] had been responsible reflected what was happening in the world of twentieth century avant-garde music, and it was through Hammer’s adventurous approach to film music that popular audiences had been, and continue to be, exposed to musical styles they might never otherwise have experienced.”

With this third book devoted specifically to music for Hammer horror films (the first was my general overview Music from the House of Hammer, in 1986; the second was Huckvale’s own James Bernard, Composer to Count Dracula in 2006), Huckvale further explores what it was that made music for Hammer’s brand of horror cinema special and so uniquely flavorful. Huckvale takes a mostly musicological approach in his analysis, grouping Hammer’s composers by style as they embodied or contrasted with the modern musical avant-garde which, according to the author, was largely introduced to the popular culture through film music such as that of Hammer. While other studios were still holding fast to Gothic romanticism (as Hammer did to an extent, mostly with the works of James Bernard and Harry Robinson) or embracing pop music styles, Hammer more than any other studio of the day encouraged composers to articulate musical modernism into their scores. Thus we have the modernism of Elisabeth Lutyens (PARANOIAC), Malcolm Williamson (BRIDES OF DRACULA), and Humphrey Searle (THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS), Mario Nascimbene (ONE MILLION YEARS, B.C.) and Tristram Cary (QUATERMASS AND THE PIT), the modern gothic sensibilities of Mike Vickers (DRACULA A.D. 1972) and John Cacavas (THE SATANIC RITES OF DRACULA), the significant serialism of Benjamin Frankel (CURSE OF THE WEREWOLF), and the innovative modernist of Paul Glass (TO THE DEVIL… A DAUGHTER) discussed in detail and as linchpins of Huckvale’s treatise. Huckvale begins his examination of Hammer film music, after introducing the studio’s three main musical directors during their horror period – John Hollingsworth, Philip Martell, and Marcus Dodds – with a chapter about classical composer Arnold Schoenberg, whose influence on musical modernism and serialism has been greater than any other composer (Schoenberg’s 12-tone system virtually defined and standardized musical modernism). What follows is then an examination of Hammer’s film music on these terms. While in the minds of many, it was 19th Century gothic romanticism that was preeminent in Hammer’s musical style; but Huckvale perceptively points out that there was more to Hammer than the inspiration of the 19th Century: “Much of the music for which [Hammer’s musical directors] had been responsible reflected what was happening in the world of twentieth century avant-garde music, and it was through Hammer’s adventurous approach to film music that popular audiences had been, and continue to be, exposed to musical styles they might never otherwise have experienced.”

James Horner: The Gift of Immortality

Antonio Piñera and Antonio Pardo Larrosa

272 pages, paperback, T & B; Edición, 2016. Spanish language.

A 272-page chronicle of the late composer and his remarkable career. Features prologues by composer/ conductor/orchestrator Conrad Pope and Varese Sarabande album producer Robert Townson. The book is currently available from Amazon Spain.

El Legado Musical De La Hammer

El Legado Musical De La Hammer

Antonio Piñera

340 pages, paperback, T & B; Edición, 2016. Spanish language.

Piñera, who co-wrote the Horner book above as well as, last year, a Spanish-language book on Miklós Rózsa, has also just released a this new 340-page book dedicated to the composers of the Hammer. The book includes forewords by Caroline Munro and David Huckvale (author of a 2008 book on Hammer Film Music). Available from Amazon Spain

Composing for the Cinema: The Theory and Praxis of Music in Film

Ennio Morricone & Sergio Miceli

Translated from Italian by Gillian B. Anderson.

295 pages, Scarecrow Press, 2013.

![]() Published by The Scarecrow Press in 2013, Composing for the Cinema: The Theory and Praxis of Music in Film is co-written by Ennio Morricone and Sergio Miceli, translated from Italian by Gillian B. Anderson. Based on a series of lectures presented by celebrated composer Morricone and musicologist Miceli on the composition and analysis of film music, which has been transposed and adapted into this 300-page book, it’s not an easy book. Its thickly worded paragraphs are extremely academic and professorial, even with Anderson’s translation into relatively simpler conversational English. Without any images or music samples, it’s not as practical a how-to manual in the way that On The Track, by Rayburn Wright and the late Fred Karlin, is – but it’s worth wading through to not only get a glimpse at Morricone’s intelligent focus on musical form but also to grasp some of the theoretical principals about making music for cinema that can then be applied through the benefit of further hands-on study.

Published by The Scarecrow Press in 2013, Composing for the Cinema: The Theory and Praxis of Music in Film is co-written by Ennio Morricone and Sergio Miceli, translated from Italian by Gillian B. Anderson. Based on a series of lectures presented by celebrated composer Morricone and musicologist Miceli on the composition and analysis of film music, which has been transposed and adapted into this 300-page book, it’s not an easy book. Its thickly worded paragraphs are extremely academic and professorial, even with Anderson’s translation into relatively simpler conversational English. Without any images or music samples, it’s not as practical a how-to manual in the way that On The Track, by Rayburn Wright and the late Fred Karlin, is – but it’s worth wading through to not only get a glimpse at Morricone’s intelligent focus on musical form but also to grasp some of the theoretical principals about making music for cinema that can then be applied through the benefit of further hands-on study.

There is much of value here indeed, preparatory to the practical part of putting pencil to paper (or finger to keyboard, as the case may be). “The composer has to make a structural analysis,” Morricone explains in Chapter 3, Production Procedures, using himself as the example. “He has to analyze the editing and cutting of the montage, the motion picture camera, and the manner in which the film is shot and runs, but above all he had to analyze the psychological makeup of the protagonists. I think not about their obvious character, but also about their thoughts, about their reflections, about their human or inhuman depth, according to the people with whom they associate. From there I arrive at compositional choices.” (p. 53). What follows in succeeding chapters, which run in detail through topics such as Audiovisual Analysis, Production Procedures, Premix and Final Mix, Compositional Elements, and an intriguing Appendix on “Writing for the Cinema: Aspects and Problems of a Compositional Activity of Our Time,” is a mix of narratives attributed to both authors and sections in which Miceli interviews Morricone for further detail and clarification (the final chapter is, in fact, an extended collection of interview Q&As that serves to conclude their analysis and ensure no loose strings are left untied in their comprehensive dissertation).